Diabetes mortality rates among Blacks are higher than white rates in all 30 of the largest U.S. cities, according to research from psychologist Joanna Buscemi at DePaul University. (iStock.com/vitapix)

Diabetes mortality rates among Blacks are higher than white rates in all 30 of the largest U.S. cities, according to research from psychologist Joanna Buscemi at DePaul University. (iStock.com/vitapix)CHICAGO — Black Americans are dying from diabetes at higher rates than their white neighbors in all of the 30 largest cities in the U.S. This finding comes from new research linking diabetes mortality rates and race using city-level data. Psychologist Joanna Buscemi of DePaul University is lead author of the study, published in the journal “Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic has increased awareness about racial health disparities in the U.S.,” said Buscemi, noting that Black Americans are suffering greater rates of mortality from both COVID-19 and diabetes. Buscemi asserts that improving policies and conditions that impact patients with diabetes could help those same individuals if they do contract the virus that causes COVID-19. Buscemi, an assistant professor in the College of Science and Health, and her co-authors found:

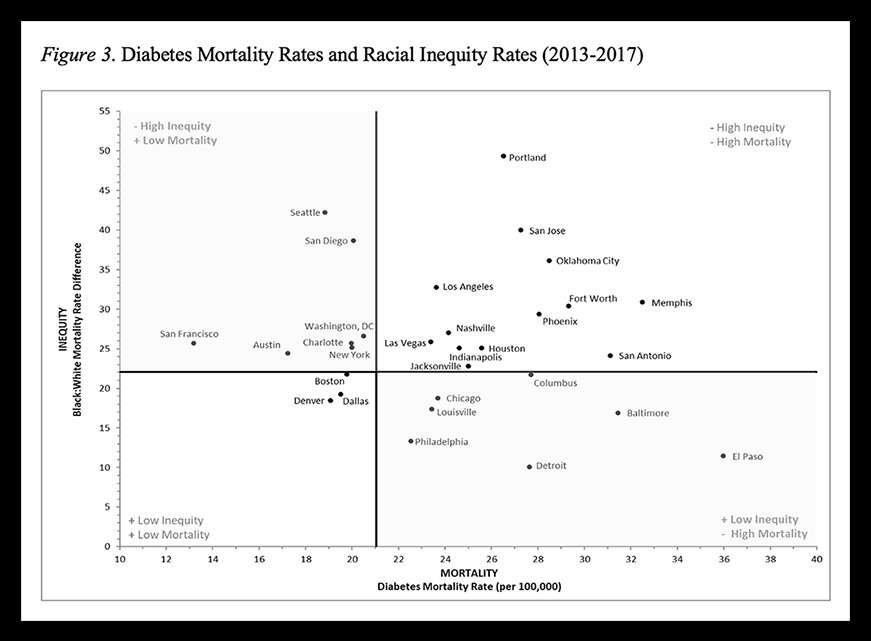

- Diabetes mortality rates among Blacks are higher than white rates in all 30 cities.

-

Diabetes mortality inequities are four times larger in some cities compared to others.

-

Only three of the 30 largest cities had low rates of diabetes mortality and inequity.

-

Washington, D.C., diabetes mortality inequities are the highest of all 30 cities.

The study is published at

http://bit.ly/diabetes_DPU. Co-authors are Nazia Saiyed and Maureen R. Benjamins at Sinai Urban Health Institute, Abigail Silva at Loyola University Chicago and Fereshteh Ghahramani at DePaul.

City-level data shows variation

Joanna Buscemi is an assistant professor of psychology at DePaul University. (Image courtesy of Joanna Buscemi)

Joanna Buscemi is an assistant professor of psychology at DePaul University. (Image courtesy of Joanna Buscemi)Examining data at a city level can inform more targeted local policy interventions and programming to promote health equity, particularly within cities with the greatest inequities, write the researchers. “Most studies do look at the U.S. overall, but that can hide these nuances and differences that exist across cities,” Buscemi said.

The scope of the problem is large overall. Diabetes affects 34.2 million people in the U.S., with millions more who are likely undiagnosed, according to the National Institutes of Health. Researchers examined city-level data from two five-year time periods. Twenty-two of the 30 largest U.S. cities had higher diabetes mortality rates than the U.S. overall. The cities with the highest diabetes mortality rates were El Paso, Texas; Memphis, Tennessee; and Baltimore.

In terms of racial inequity, researchers found some cities faring worse than others. The worst disparity was in Washington, D.C., where Black residents were almost seven times more likely to die of diabetes than their white neighbors. In several cities, those inequities are increasing, including Chicago, Los Angeles and Oklahoma City. Bright spots included Louisville and Phoenix, which showed a statistically significant decrease in diabetes mortality racial inequities over time.

Diabetes and policy during COVID-19

Black Americans are facing higher levels of COVID-19 mortality, and they also suffer from diabetes at higher rates than whites. One area that Buscemi believes could make a big difference, quickly, is to place a cap on the cost of insulin. “If you can’t afford insulin, and your disease is not managed, then it’s going to have more of an impact if you contract COVID,” Buscemi said.

Other categories of policymaking that the researchers point to include addressing income inequality, affordable health care, food deserts, and accessing places to safely exercise. Buscemi notes that these are social determinants of health, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes as “conditions in the places where people live, learn, work and play that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes.”

Buscemi conducted this research as one of the first collaborations in a group of Sinai Urban Health Institute-DePaul University Research Fellows. Researchers from Sinai and DePaul are engaging with community members, leaders and organizations in research and action to assess and address health and social inequities. As COVID-19 has raised awareness about health disparities, Buscemi hopes this work will help to close the gaps: “DePaul faculty have broad expertise across disease presentations, and with Sinai Urban Health Institute’s experience working with communities to combat inequities in Chicago and nationally, it is a perfect partnership to tackle systems that perpetuate racial inequities.”

Learn more about their work at

http://bit.ly/DPU_Sinai.

Cities that rated high on diabetes morality and low on equity were categorized as worst-performing cities. Those that rated low on diabetes mortality and high in equity were among the best-performing cities. (Image courtesy of Joanne Buscemi)

Cities that rated high on diabetes morality and low on equity were categorized as worst-performing cities. Those that rated low on diabetes mortality and high in equity were among the best-performing cities. (Image courtesy of Joanne Buscemi)

###

Source:

Joanna Buscemi

JBUSCEM2@depaul.edu

Media contact:

Kristin Claes Mathews

kristin.mathews@depaul.edu

312-241-9856 (cell)