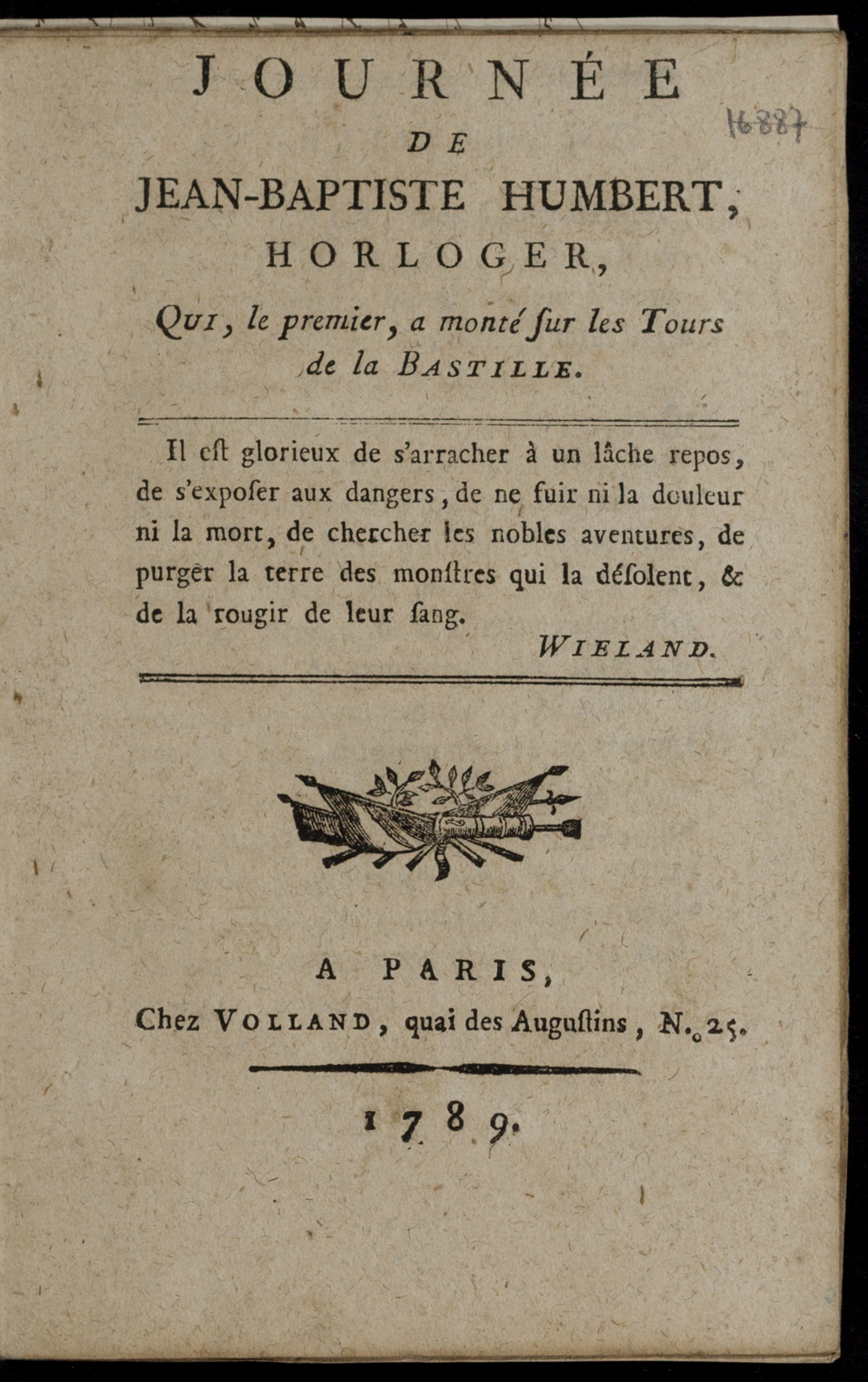

The cover of an original 18th-century pamphlet written by Jean-Baptiste Humbert. The pamphlet is just one of several that was translated from French to English by Pascale-Anne Brault's French translation class during the fall quarter. (The Newberry Library, Chicago)CHICAGO — Students in Pascale-Anne Brault’s French translation class often

feel they are back in 18th-century France, during the French Revolution,

because of an unusual class project with Chicago’s Newberry Library.

The cover of an original 18th-century pamphlet written by Jean-Baptiste Humbert. The pamphlet is just one of several that was translated from French to English by Pascale-Anne Brault's French translation class during the fall quarter. (The Newberry Library, Chicago)CHICAGO — Students in Pascale-Anne Brault’s French translation class often

feel they are back in 18th-century France, during the French Revolution,

because of an unusual class project with Chicago’s Newberry Library.

The Newberry, an independent research library, has a

collection of more than 30,000 documents from that volatile era — pamphlets

from aristocrats, clergy, commoners and political activists. Some 20 of

Brault’s students and two DePaul alumni are paired up with an original French

Revolution era pamphlet to translate into English for the first time. Their

final translations ultimately will go online for researchers and others around

the world to access.

“The document I’m working on with my translation partner,

Madelyn Colvin, is a personal account of Jean-Baptiste Humbert, who stormed the

Bastille July 14, 1789,” said Owen Ostermueller, a junior pursuing a degree in

French.

“There are no history books, no secondary sources. I get to

study and interact with a document written by someone who took part in a

defining moment of Western history. For someone that geeks out over revolution,

politics and philosophy, especially if any of them are French, working with a

document so closely connected to the actual French Revolution is just about as

interesting as it gets. If you Google the Bastille, you can see the drawbridge

that Humbert talks about crossing and the towers he talks about climbing, it

gives a great new layer of perspective. It’s been so humbling and exciting to

play a part in bringing this intimate piece of history to a broader audience

through translation,” Ostermueller said.

The pamphlets represent opinions of factions that opposed

and defended the monarchy, said Brault, a professor in DePaul’s modern

languages department. They range from letters to the general assembly, to

plays, music and verdicts from the courts. One document comes from a prisoner

pleading that he didn’t receive due process or a fair trial. Another suggested

how ending slavery in the Caribbean Sea territory of Martinique would stimulate

the economy.

“The selection of texts was extremely varied in order to

provide insights into the turbulent years of the French Revolution from as many

perspectives as possible,” said Brault. “They voice the concerns of an entire

nation trying to rethink itself in the wake of the Revolution.”

Most interesting perhaps are works described by Brault as

some of the first “feminist manifestos.” These include a Declaration of the

Rights of Women that seeks to match the Declaration of the Rights of Man of

1789, a letter asking for equal punishment for husbands and wives who commit

adultery, and equal education for boys and girls.

The project offers a complicated set of challenges when deciphering

language from 18th-century France, said Brault.

“Terminology has evolved in meaning over time,” she said. “Students

have had to use dictionaries of the time period and look at the history of

certain terms. They’ve also had to read documents in English of the same time

period in order to provide historically accurate translations. Some documents use

very technical legal terminology, others were written by people with little

formal education so the original sometimes includes mistakes and defective

syntax.”

Another challenge were the letters from the alphabet, noted

Brault. In 18th-century France, the letter F was used the same way an S would

be in 2017. However, the letter F could also just mean F, so the students had

to determine if the letter should be an F or an S. For example, “je prévois que

l’autorité du roi, comme le premier légiflateur de la loi, le forceroit

d’interpofer fa puiffance fupérieure” in 1789 would read “je prévois que

l’autorité du roi, comme le premier législateur de la loi, le forcerait

d’interposer sa puissance supérieure” in contemporary French. In English, that

sentence means “I foresee that the authority of the King, as the first legislator

of the law, might have to use his superior powers to intervene.”

“Translating these 1789 pamphlets has been a great way to

learn more about the French Revolution, a fascinating period in French history,”

said Brault. “These texts provide

some context for France’s first attempt to create a new type of society, one

that would embody democratic ideals. Ultimately, they also cause us to rethink

the current state of democracy in the world. A translation is never just a text,

it has a context and that context can be a platform for the study of the

language, history and values of a culture, as well as its political and

intellectual legacy.”

###

Source:

Pascale-Anne Brault

pbrault@depaul.edu

773-325-1867

Media Contact:

Russell Dorn

rdorn@depaul.edu

312-362-7128