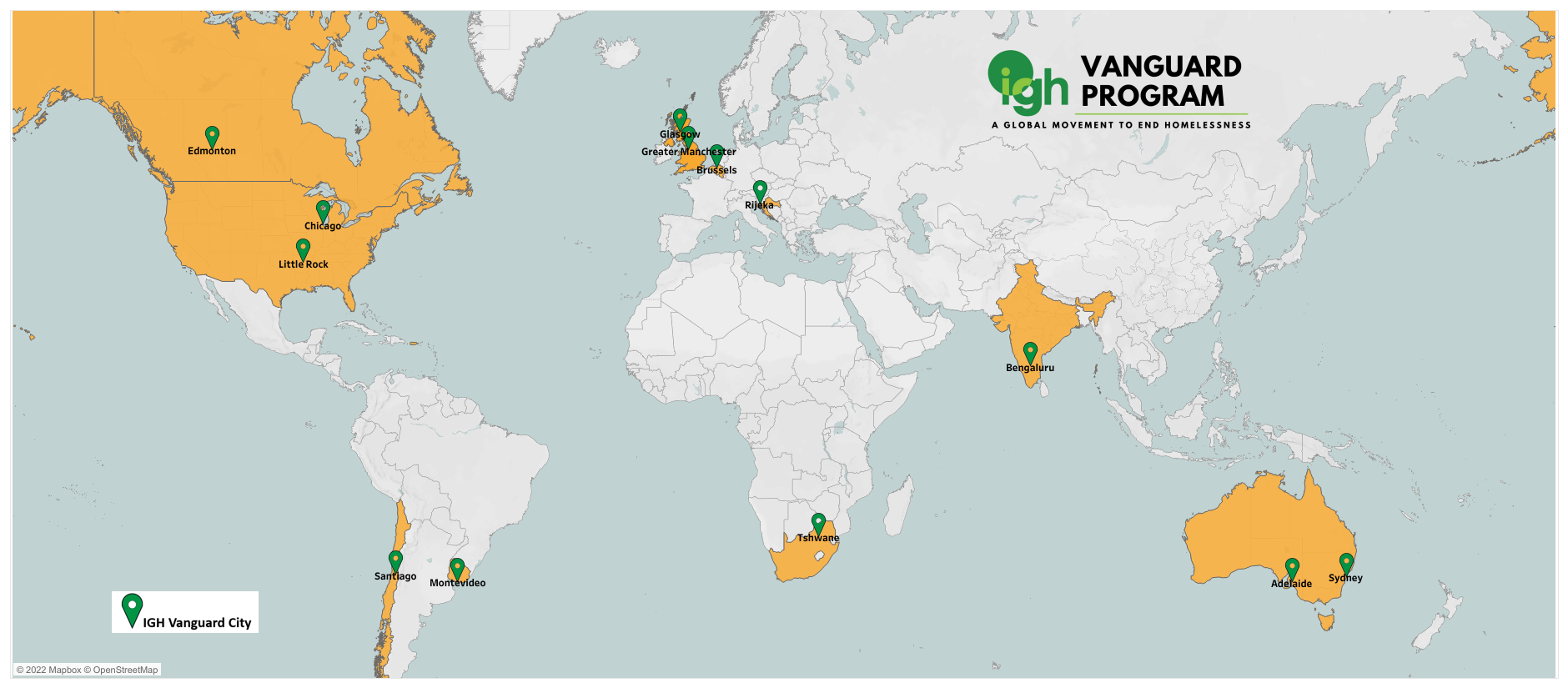

A map of the 13 “Vanguard Cities” that committed in 2017 to a target of either ending or reducing street homelessness by December 2020 through the “A Place to Call Home" initiative. (Courtesy of DePaul University's George and Tanya Ruff Institute of Global Homelessness)

A map of the 13 “Vanguard Cities” that committed in 2017 to a target of either ending or reducing street homelessness by December 2020 through the “A Place to Call Home" initiative. (Courtesy of DePaul University's George and Tanya Ruff Institute of Global Homelessness)CHICAGO — In the first global initiative aimed at ending street homelessness, 13 cities around the world, including Chicago, discovered key ingredients for success along with common systemic barriers. This included an overreliance on charity and faith groups for service delivery in some cities, according to new research from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The research corroborates the efforts of “

A Place to Call Home,” an initiative launched by DePaul University’s George and Tanya Ruff Institute of Global Homelessness (IGH) in 2017. “A Place to Call Home” was the first concerted effort to support cities across the globe as they attempted to eradicate street homelessness.

“Homelessness around the world has far more similarities than differences, as this international comparative study shows,” said Lydia Stazen, director of the Ruff Institute of Global Homelessness. “This study provides us with rich global insights that we can apply in our local communities in our efforts to end homelessness.”

Founded in 2014, IGH is the first organization to focus on homelessness as a global phenomenon with an emphasis on those who are living on the street or in emergency shelters. It is a partnership between DePaul University and Depaul International (London), with the latter providing direct services for people experiencing homelessness in the U.K., Ireland, Ukraine, Slovakia, Croatia, the U.S. and France.

The institute gathered an initial cohort of 13 “Vanguard Cities” that committed to a target of either ending or reducing street homelessness by December 2020. Chicago, Illinois, Little Rock, Arkansas, and Edmonton, Canada, served as the North American Vanguard Cities. Over half of the cities (Adelaide, Australia, Glasgow, Scotland, Greater Manchester, U.K., Montevideo, Uruguay, Santiago, Chile, Sydney, Australia, and Tshwane, South Africa) achieved reductions in street homelessness.

The goals set by these cities ranged from ending street homelessness entirely in their city or ending it in a particular neighborhood or within a certain subpopulation to achieving specified proportionate reductions of various kinds.

The participating North American cities saw mixed results. Of the American Vanguard Cities, Chicago saw greater results thanks largely to the city’s tracking and management of the homeless population. However, COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and safety protocols likely affected the results of each of the city’s efforts.

North American cities noted a racial aspect to their homeless populations. Chicago and Little Rock saw large numbers of Black males experiencing street homelessness; Edmonton’s Indigenous population experienced similar fates. Even as people of color face homelessness more, programs lack dedicated, tailored plans for these groups, researchers found.

“While there are clear country-specific challenges that need to be overcome, this first global initiative on tackling street homelessness has highlighted the need to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach, towards more specialized interventions that target specific subgroups. Appropriate services for women, children, older people and other vulnerable groups, as well as culturally sensitive responses to Indigenous people and other groups affected by racial and associated forms of prejudice are essential,” said Suzanne Fitzpatrick, a professor and director of Heriot-Watt’s Institute for Social Policy, Housing and Equalities Research, who led the international research team.

Of the cities that achieved success, the presence of a lead agency was key to driving efforts. The study also found that coordinated entry to homelessness services, which identified, profiled and tracked the people affected, coupled with investment in specialized and evidence-based interventions, were most beneficial. These included assertive street outreach services, individual case management and the “Housing First” approach, which is a policy to offer permanent housing first to folks who are homeless before working on supportive services.

The initiative found common barriers to progress across multiple countries and cities, including a lack of preventative interventions to tackle street homelessness, pressure on affordable housing and insufficient resources, especially in cities in the Global South.

An overreliance on communal shelters represented an approach limited to “managing” rather than reducing street homelessness. With many local and national governments failing to take responsibility for the systemic changes needed to protect vulnerable people, there was often a dependence on voluntary and faith groups to provide crisis services. However, the direct involvement of some religious denominations was found to discourage access for some people, while adding to the conditions attached for those seeking support.

Aggressive enforcement interventions by some police and city authorities, especially in North America and the Global South, and documentary and identification barriers, were also found to be counter-productive to attempts to reduce street homelessness.

The independent evaluation of the IGH initiative, funded by Oak Foundation and delivered by Heriot-Watt in partnership with the GISS institute in Bremen, Germany, monitored progress towards the numerical goals set by each city and, crucially, drew out the core components of successful interventions that may be relevant to other locations.

The involvement of IGH was viewed as instrumental in driving up the local profile, momentum and level of ambition attached to reducing street homelessness in the Vanguard Cities. It is recommended that work with future cohorts of cities should focus on more tailored forms of support specific to the needs of each city, and to different types of stakeholders, particularly frontline workers.

###

DePaul Media Relations:

312-241-9856