CHICAGO — Forests in North America create a ripple effect in the ecosystem when trees occasionally reproduce synchronously en masse — a process called mast seeding. New research published in the journal Nature Plants from Jalene LaMontagne at DePaul University reveals a previously unseen spatial pattern in mast seeding that may help ecologists understand population dynamics at large scales.

Jalene LaMontagne is an associate professor of ecology at DePaul University. (Image courtesy of Jalene LaMontagne)

Jalene LaMontagne is an associate professor of ecology at DePaul University. (Image courtesy of Jalene LaMontagne) While other ecologists have studied relationships between mast seeding and more local weather patterns, LaMontagne and her colleagues looked at continent-wide data. They found at a large geographic scales greater than about 2,000 kilometers (1,250 miles), there is a negative or opposite pattern occurring. When white spruce trees in the western half of North America are having a fruitful year, production tends to be sparse in the East, and vice versa. The researchers refer to this as an ecological dipole.

“Researchers have observed that if you were at a location, trees close to you are going to be behaving similarly,” said LaMontagne, an associate professor of ecology in DePaul’s College of Science and Health. “We found that not only does the correlation decline with distance, it gets negative. So trees are doing opposite things on different sides of the continent.”

In any given year, tree species such as oaks or spruce tend to either produce all their seed together at a local scale, or they do not. This pattern of tree reproduction, in turn, impacts the survival of animal populations that use the seeds as food.

By zooming out, looking at a single species, and using weather data, they found a pattern that may make it easier to predict where large reproductive "mast events" will occur within any given year.

This aligns with long-observed patterns among seed-eating birds that mirror climate dipoles such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which creates opposite weather patterns in the East and West. “This potentially fulfills the missing link,” said LaMontagne. “By using continent-wide data, we were able to better predict where trees in forests will reproduce, which may influence where birds of different species will show up at backyard feeders looking for food.”

This is among the largest studies of its kind in mast-seeding research, with data compiled from sites covering distances over approximately 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles), said LaMontagne. The range of white spruce spans North America in the boreal forest — growing at high latitudes from the Northwoods in Wisconsin to the arctic. White spruce seeds are food for many species of small mammals, birds and insects, write the researchers. The ecologists drew from 68 datasets about white spruce reproduction collected between 1985 and 2014, measuring across the continent from the northwest in Alaska to New Brunswick, in eastern Canada.

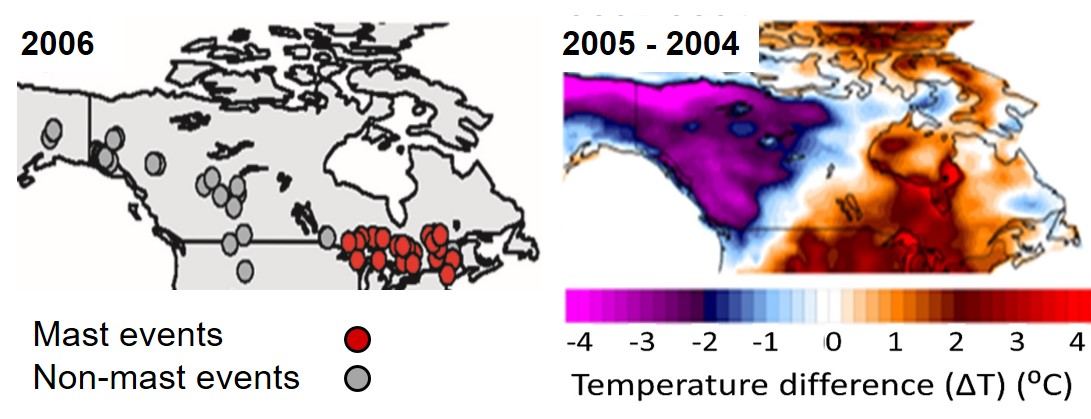

Ecologist Jalene LaMontagne and her colleagues created maps of differences in mean July temperature in two years (e.g., 2005 minus 2004) and mast-event occurrence the next year (2006) across North America and found significant overlap that could help predict where trees will reproduce in a given year. (Image courtesy of Jalene LaMontagne)

Ecologist Jalene LaMontagne and her colleagues created maps of differences in mean July temperature in two years (e.g., 2005 minus 2004) and mast-event occurrence the next year (2006) across North America and found significant overlap that could help predict where trees will reproduce in a given year. (Image courtesy of Jalene LaMontagne) Turning next to weather data, LaMontagne discovered she could map the differences in July temperatures and predict where mast seeding events would occur. The relationship between summer weather and mast seeding was “striking” across the continent.

“Hotter weather in July, when tree buds differentiate into vegetative or reproductive buds, compared to July of the previous year was a strong predictor of where mast events will occur,” said LaMontagne.

The researchers used the Daymet daily surface weather and climatological summary dataset, which draws from thousands of weather stations throughout North America. Daymet is supported by NASA and the Department of Energy.

And while weather in a specific area remained the strongest predictor for a mast-seeding event, a strong pattern also emerged at regional to continental scales.

“What we showed is asynchrony — if there are a lot of cones on trees in the eastern part of North America, there aren’t a lot in the west,” said LaMontagne.

Co-authors of the study are Ian S. Pearse of the U.S. Geological Survey; David F. Greene of Humboldt State University; and Walter D. Koenig of Cornell University.

The full text of the article, “Mast seeding patterns are asynchronous at a continental scale,” is available at

https://rdcu.be/b3OJX.

Funding for this research was provided by NSF grants DEB-1745496 and DEB-1926341 to LaMontagne and NSF grant DEB-1256394 to Koenig, as well as funding from the McIntire–Stennis program and a series (2005–2014) of NSERC grants to Greene.

###

Source:

Jalene LaMontagne

jlamont1@depaul.edu

Media contact:

Kristin Claes Mathews

kristin.mathews@depaul.edu

312-241-9856 mobile