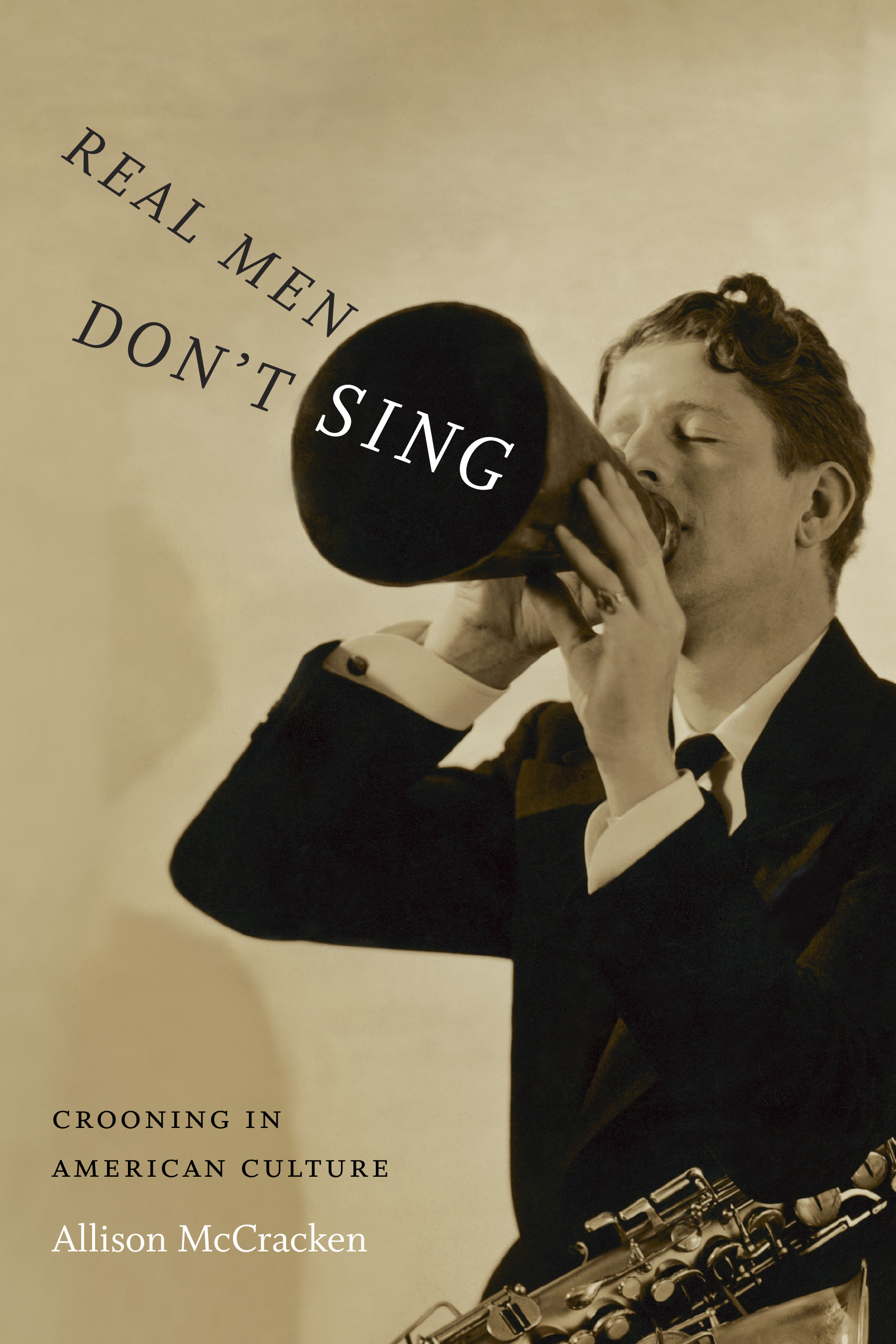

Crooning singing is the beginning of pop music, explains Allison McCracken, an expert in American popular culture, media and gender. McCracken, who teaches American Studies at DePaul University, will discuss her book “Real Men Don’t Sing: Crooning in American Culture” May 27.

Crooning singing is the beginning of pop music, explains Allison McCracken, an expert in American popular culture, media and gender. McCracken, who teaches American Studies at DePaul University, will discuss her book “Real Men Don’t Sing: Crooning in American Culture” May 27. CHICAGO — Before Justin Timberlake or Frank Sinatra, a generation of male singers in the 1920s pioneered crooning on the radio. Allison McCracken, an expert in American popular culture, media and gender, explores the topic in her book “Real Men Don’t Sing: Crooning in American Culture.”

McCracken, an associate professor in American Studies at DePaul University, will discuss her book May 27 from 1-3 p.m. at the John T. Richardson Library, 2350 N. Kenmore Ave., Room 400, on the Lincoln Park Campus.

In this Q&A, McCracken discusses the role of female fans, singers blurring gender lines and how today’s crooners stack up to the 1920s originals.

Q. What’s the definition of a crooner?

A. Since the late 1920s, a crooner has been understood as someone, usually a man, who sings a love song into a microphone, most popularly in recordings or over the radio. The current dictionary definition is “to sing popular, sentimental songs in a low, smooth voice, especially into a closely-held microphone.”

There have been various meanings of crooning, from its first development in the United States, derived from Scottish and Irish usage, as a term to describe a soft, low, intimate kind of singing. It became most associated with the mammy figure of 19th century minstrelsy, singing softly to her white charges or her own children. Generally, it was associated with maternal figures and mother and child relationships until the turn of the century, when it was culturally detached from mothering and minstrelsy and instead used as a term for romantic courtship behavior between men and women. With broadcasting, this intimate sound of courtship began to be communicated from one singer to millions of people, and thus the crooner was born.

Q. Why were crooners so important to pop music and American culture in the 1920s and 1930s?

A. Crooning singing is the beginning of pop music. Before the advent of crooners, pop was considered any type of performance that was cheaply priced, commercial and low culture. When crooning singing became immensely popular, the term “pop” narrowed to describe the particular kind of singing they did: commercial, generic, lowbrow in its mass address and appealing to women.

Rudy Vallée was America’s first pop idol because his stardom established the structures and behavior we associate with pop idols, including the swooning crowds and policing we associate with Sinatra, Elvis and the Beatles. The backlash against his popularity in the early 1930s set the blueprint for every pop idol to follow. His commercial success and influence had to be contained through his artistic devaluation, the ridicule of his “hysterical” female audiences, and his perceived emasculation. This has been the dominant framework for evaluating male pop idols ever since, from Vallée through One Direction.

Without female fans, crooning and pop music would never have been born, says author Allison McCracken. (Photo courtesy of the author) Q. How did these singers’ voices and attitudes blur gender lines?

Without female fans, crooning and pop music would never have been born, says author Allison McCracken. (Photo courtesy of the author) Q. How did these singers’ voices and attitudes blur gender lines?

A. They did have many qualities perceived as feminine in the 1920s, although these were not considered effeminate at that time. For example, they dressed fashionably, were clean-cut, often wore makeup and ironed, curled or pomaded their hair. They loved women and sang intimate love songs primarily for and directly to them.

Vocally, most were tenors who sang using their head voices rather than chest voices. Their soft, smooth, breathy, conversational style, their sensitivity and vulnerability, and the fact that they frequently positioned themselves lyrically as passively longing for their dream girl — was read as feminine-coded to varying degrees. It’s important, however, that these qualities were not yet widely perceived as emasculating in the 1920s. Crooners didn’t necessarily blur gender lines in the 1920s so much as the fact that gender lines narrowed around them in the early 1930s in a way that newly marked them as insufficiently masculine.

The crooners who were stigmatized were specifically white, male stars. In part, this is because men of color were segregated out of star positions in national broadcasting and recording (they could not be pop stars). The emasculation of white men was seen as a major problem because they were meant to represent the nation. It was much more acceptable for men of color to sing in high pitches and to show sensitivity and strong emotion, and their sexuality as popular entertainers remained largely unimportant to white authorities.

Q. Who are some famous crooners, and who are others that we might not have heard of?

A. Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra are the most famous crooners. Rudy Vallée was the first crooning idol, although he is less well-known today. Since then, many singers known as pop or rock or country have employed crooning styles of singing, which is basically called “pop” now, although on singing competitions, the word “crooner” comes up when young men dress in classical 1940s-50s styles (jackets) and sing love songs, so it is still used specifically in that way.

Barry Manilow, Michael Bublé and Harry Connick Jr. are frequently referred to as crooners in this particular style, whereas boy band members are not, although what they’re doing is crooning and they certainly are stigmatized in the way crooners were.

Q. Why was female fandom important to crooning?

A. One of the book’s major arguments is that both men and women initially loved crooning sounds, and, indeed, the crooning style of singing in the 1920s was popular across lines of class, race, ethnicity and gender. Vallée’s original fan letters, when he first became popular over New York stations in 1928, show that he was popular with both sexes. Men felt no discomfort in enjoying his music, particularly lower class men who came from ethnic backgrounds (Irish, Italian and Jewish) in which young male singers were highly valued. However, women were always more publicly demonstrative in their appreciation of Vallée as he began more public appearances. Powerful New York radio columnists continually asserted that men hated Vallée and that he was causing strife between husbands and wives. When Vallée and others began to be increasingly stigmatized as emasculated, this homewrecker narrative took root culturally as gospel. Men who liked crooners, therefore, were either culturally erased or stigmatized.

Although the backlash against crooners stigmatized crooning forever, female fans continued to ensure its survival because it was very profitable. Thus, crooners — pop idols — have persisted despite their cultural devaluation and those of their audiences. Without female fans, the pop idol would never have been born and would not have persisted.

###

Media Contact:

Kristin Claes Mathews

kristin.mathews@depaul.edu

312-241-9856