DePaul University political scientist Kathleen Arnold writes that domestic violence is a political issue, not just a personal one. She is available for interviews on the topic. (Photo by Rene Ruiz)

DePaul University political scientist Kathleen Arnold writes that domestic violence is a political issue, not just a personal one. She is available for interviews on the topic. (Photo by Rene Ruiz)Political scientist Kathleen R. Arnold believes Americans do not respond effectively to domestic violence, and that solutions are not just personal but political. An instructor at DePaul University, Arnold has published extensively on issues affecting marginalized populations, such as immigration and homelessness. In her latest book, “Why Don't You Just Talk to Him?: The Politics of Domestic Abuse,” Arnold argues against systems that treat domestic abusers and targets of domestic abuse equally.

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, and in this Q&A, Arnold discusses how better approaches may be found in unexpected places, including the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s response to domestic violence among refugees. Arnold is available for interviews and can be reached at karnol14@depaul.edu.

Q. Your research tends to focus on marginalized populations, including immigrants and people experiencing homelessness. How do you define domestic violence as a political issue, as opposed to a personal issue?

A. Like racism and other forms of bias, intimate violence clearly happens in interpersonal contexts. Nevertheless, social attitudes, police enforcement (or lack thereof) and laws all contribute to encouraging or tolerating abuse. Ironically, egalitarian attitudes like “it takes two to tango” make us blind to inequality in relationships in a variety of political and socio-economic contexts. When we view all relationships between men and women in egalitarian terms, we then often focus on the target of abuse rather than the perpetrator. We ask: “Why did she stay? Why didn’t she seek help?” And we hold her responsible if children witnessed any abuse. Counter-intuitively, this egalitarian attitude then leads to an over-focus on targets of abuse, while ignoring abusers’ actions and destructive tendencies. Like bullying, we must also recognize that abusers act out of a pleasure in controlling someone else. If our culture were to recognize this, responses would change and abusers may be held accountable for their actions. Targets of abuse might call the police more, and society might demand fair sentencing and stop blaming women trapped in these situations.

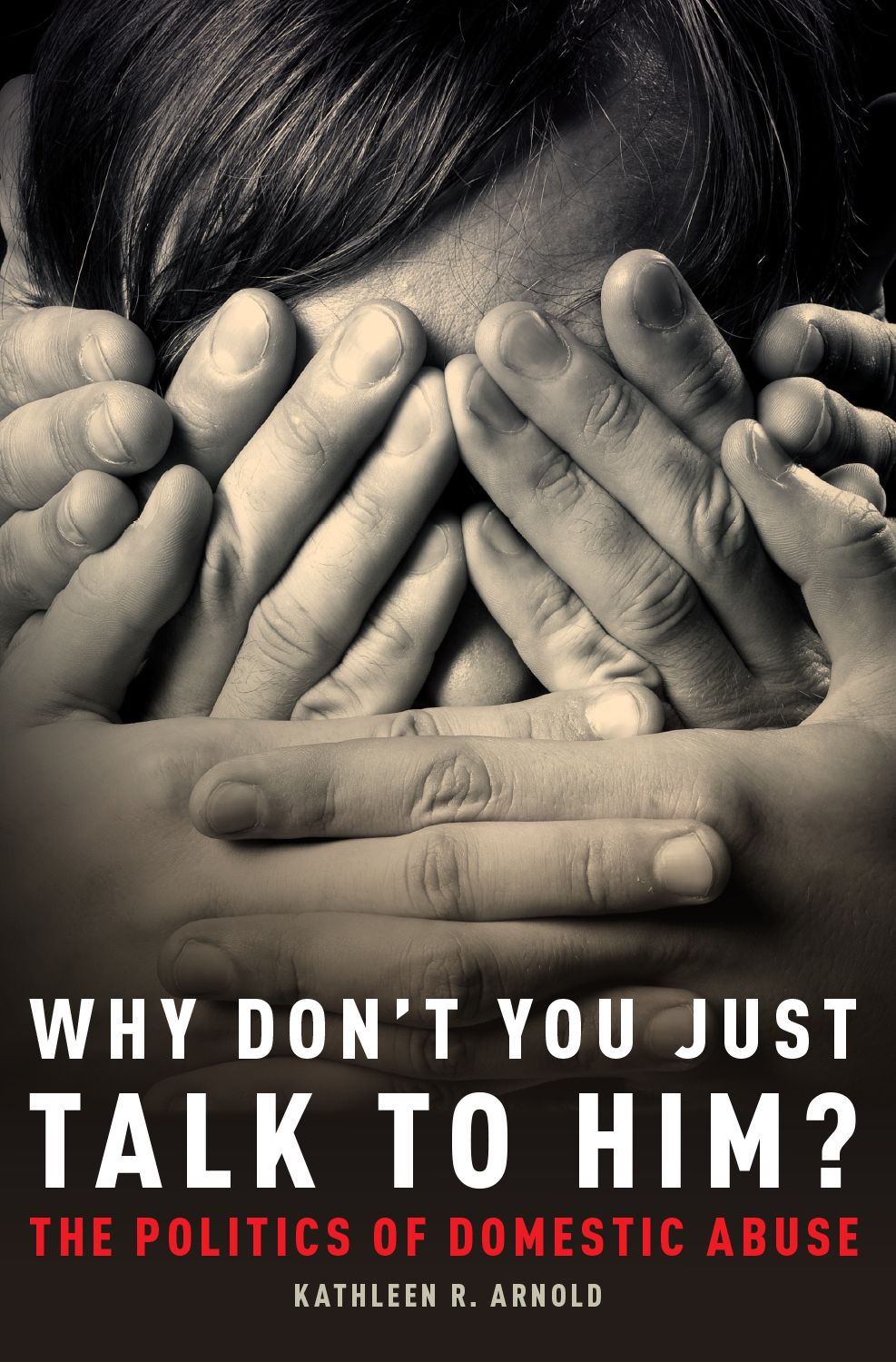

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, and author Kathleen Arnold is available to discuss the political and cultural issues that perpetuate domestic violence. In her latest book, “Why Don't You Just Talk to Him?: The Politics of Domestic Abuse,” Arnold argues against systems that treat domestic abusers and targets of domestic abuse equally. (Image courtesy of Oxford University Press)

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, and author Kathleen Arnold is available to discuss the political and cultural issues that perpetuate domestic violence. In her latest book, “Why Don't You Just Talk to Him?: The Politics of Domestic Abuse,” Arnold argues against systems that treat domestic abusers and targets of domestic abuse equally. (Image courtesy of Oxford University Press)

Q. What are some current policies or attitudes that ignore the realities of domestic violence?

A. What I have found is that while most abusers can act with near-impunity, targets of abuse are often arrested, lose custody of their children and, even in the best of circumstances, are asked to flee to a shelter. They often see more jail time than perpetrators, and abusers succeed in securing child custody more often than targets of abuse. While study after study has demonstrated that targets of abuse understand and can predict the behavior of their abusers better than any “expert,” we continue to ignore their claims and treat them as if they are incapable of making decisions. More broadly, there is little unified policy response to domestic violence and quite a lot of discretion by law enforcement. While I believe societal attitudes must change, the state must develop a much better response to intimate partner violence than it is currently doing. We must also understand economic causes and consequences of abuse. For example, an abuser can interfere with his target’s ability to work. Rather than firing an employee — as has happened when employers learn their workers are being harassed and threatened — we need to realize that targets need support and understanding. We need to focus our attention and even blame on abusers, instead.

Q. Is there an example from your research that illustrates how policy shifts can help, or hurt, victims of domestic violence?

A. What I suggest in my new book is policies that the U.S. extends to refugees who arrive in our country should be adopted for all of our residents. This issue is not merely personal but is inextricably bound to political dynamics, both informal and formal. Refugee standards are not perfect as they are currently practiced, but the model formed by the Department of Homeland Security recognizes that women refugees, as a group, are subjected to more interpersonal violence than men. Refugee standards also recognize when a “weak civil society response” contributes to abuse, from a government’s abuse of power to sexist laws in the country of origin. And these standards also ask how and why the male partner felt entitled to abuse his partner, connecting it to social beliefs.

If we were to look at all domestic abuse situations in the U.S. this way, it would allow mainstream society to understand how abusers are often rewarded, not held accountable by the state and, perhaps most importantly, that intimate abuse is widespread, systematic in certain regards, and thus is a technique of gender control.

The Ray Rice case — in which American audiences viewed him attacking his wife in an elevator and then learned that both individuals were arrested — is an example of how far we are from truly effective response and support for targets. The societal response was perhaps even sadder — comments on Facebook for example, conveyed pity but also condemnation of his now-wife. People said: She needed therapy; she should leave; she was a victim of herself. What about him?

###

Source:

Kathleen Arnold

karnol14@depaul.edu

Media Contact:

Kristin Claes Mathews

kmathew5@depaul.edu

312-241-9856