The month of May and Mother's Day can be such an uplifting time. For many, it stands as a reminder to show love to biological, adopted and chosen mothers. Throughout this pandemic many of us have been separated from the mothering bodies that have given us strength and encouragement throughout our lives. Even as many of us engaged in a time of reunion and celebration this month, it is important to remember those who did not have access to their loved ones -- mothers who sit on the outskirts of familial and societal belonging.

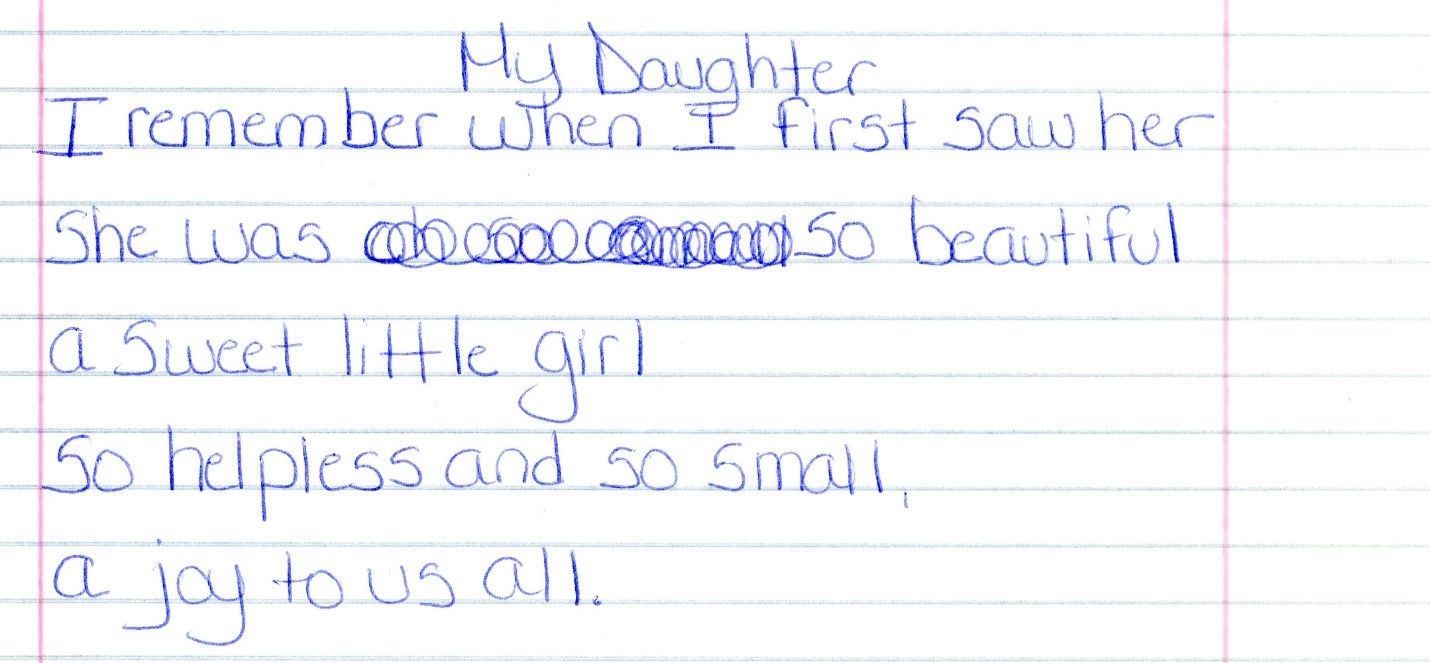

A creative writing sample from the WWIP. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

A creative writing sample from the WWIP. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)Ann Folwell Stanford, a poet and professor emerita at DePaul, committed much of her work to creatively theorizing “beyond the razor wire." She independently taught creative writing at the Cook County Department of Corrections for several years before designing DePaul classes with the School of New Learning, now the School of Continuing and Professional Studies. These classes facilitated students' involvement in the poetic creation and learning of women affected by the criminal legal system. The courses were setup as a larger project called the, "Women, Writing, and Incarceration Project."

“As students experience the 'crossing over' that going into a penal institution represents and talking with incarcerated, or formerly incarcerated, women, assumptions are shaken and space is created for radically new learning to occur," Stanford said of the project's importance.

The assumptions Stanford referred to are multifaceted, but most directly engage with perceptions of who exists in penal institutions. What are they like and what are their stories?

At the time of the WWIP classes (2001-05), project statistics reflected nearly 98,000 women experienced incarceration in the U.S., while more than 2,500 were incarcerated in Illinois. J ust over 80% of these women were mothers. In 1999, around 5% of mothers were pregnant when they were affected by the criminal legal system. Over half of all women in prisons and jails had experienced one or more interlocking systemic oppressions such as racialized and gendered violence, poverty and abuse. These were the women WWIP fought to make visible.

However, in recent years these numbers have shifted. According to Prison Policy Initiative, more than two million women experience jail time in the U.S. each year and an estimated 80% are mothers. Additionally, an estimated 60% of all women in prisons are mothers and nearly 150,000 of these women spent Mother's Day without access to their children in 2021. These numbers do not account for the many other mother figures, including and beyond cis women, who also experience incarceration.

Stanford, students and partner organizations provided a space for the mothering bodies society does not recognize or accept. She advocated for the resources to support the creative acceptance of each woman.

“Resistance to oppression takes many forms. One of those is writing behind the razor wire, interrupting the official or dominant discourse to write, 'I exist as a human being, as a woman, a mother, a child, a lover,'" she said.

This statement and the work it was oriented around revealed the humanity each writer, mother, friend and survivor maintained despite their incarceration. Stanford was not fighting to procure sympathy for mothers affected by incarceration, but rather to put creative theorizing into practice and maintain the dignity and inherent worth each person deserved. Considering the impact of the carceral state, Stanford's framework offers meaningful insights on how to resist state-sanctioned disembodiment.

Creative writing gave mothers in the program space to engage with their stories of selves and imagine liberation. Throughout the course of this program Stanford presented at several conferences. Over thirty anthologies were created both within correctional facilities and group homes, and nearly 400 handwritten poems were created. These poems, along with other writings and materials related to the project, make up the Women, Writing and Incarceration Project records, held in DePaul Special Collections and Archives.

In her writing and speaking, Stanford deeply engaged with the intrinsic humanity of folks affected by the prison-industrial-complex. She repeatedly challenged readers and listeners to rethink their opinions and interrogate preconceived notions about the type of person experiencing incarceration. In one conference exercise she encouraged participants to “write down one image" that came to mind when they thought about the criminal legal system. Here, Stanford asked participants to analyze what disparities existed in their pictures and assumptions when it came to imprisonment? What did bodies affected by incarceration look like? As she attempted to illuminate bias and dislodge notions of which people seem most deserving of punishment or visibility, based on race, gender or socioeconomic status, she created space to re-evaluate state-sanctioned narratives of disembodiment.

Below are some ways to get involved and DePaul community resources that further engage in the work of abolition, policing and creatively theorizing beyond incarceration:

Rebekah Otto is the processing archives assistant in the DePaul University Library.