(National Park Service/Scarlett Farley)

DePaul students in Jane Baxter's "Anthropology 390: Citizen Historians" course. (Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

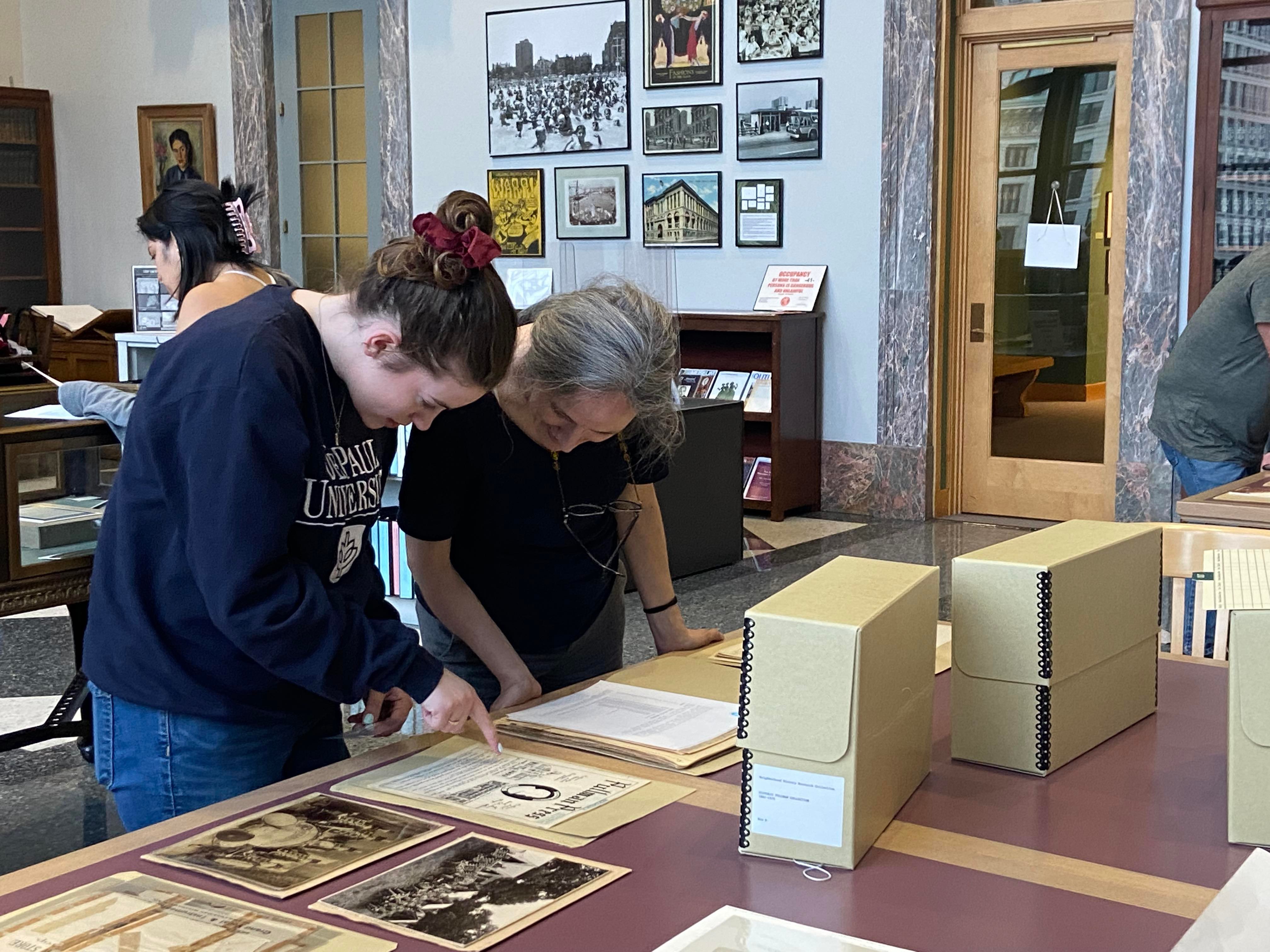

DePaul 2023 alumna Grace Brown (left) and Pullman resident Rebecca Conant partnered together to research Conant's house history. (Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

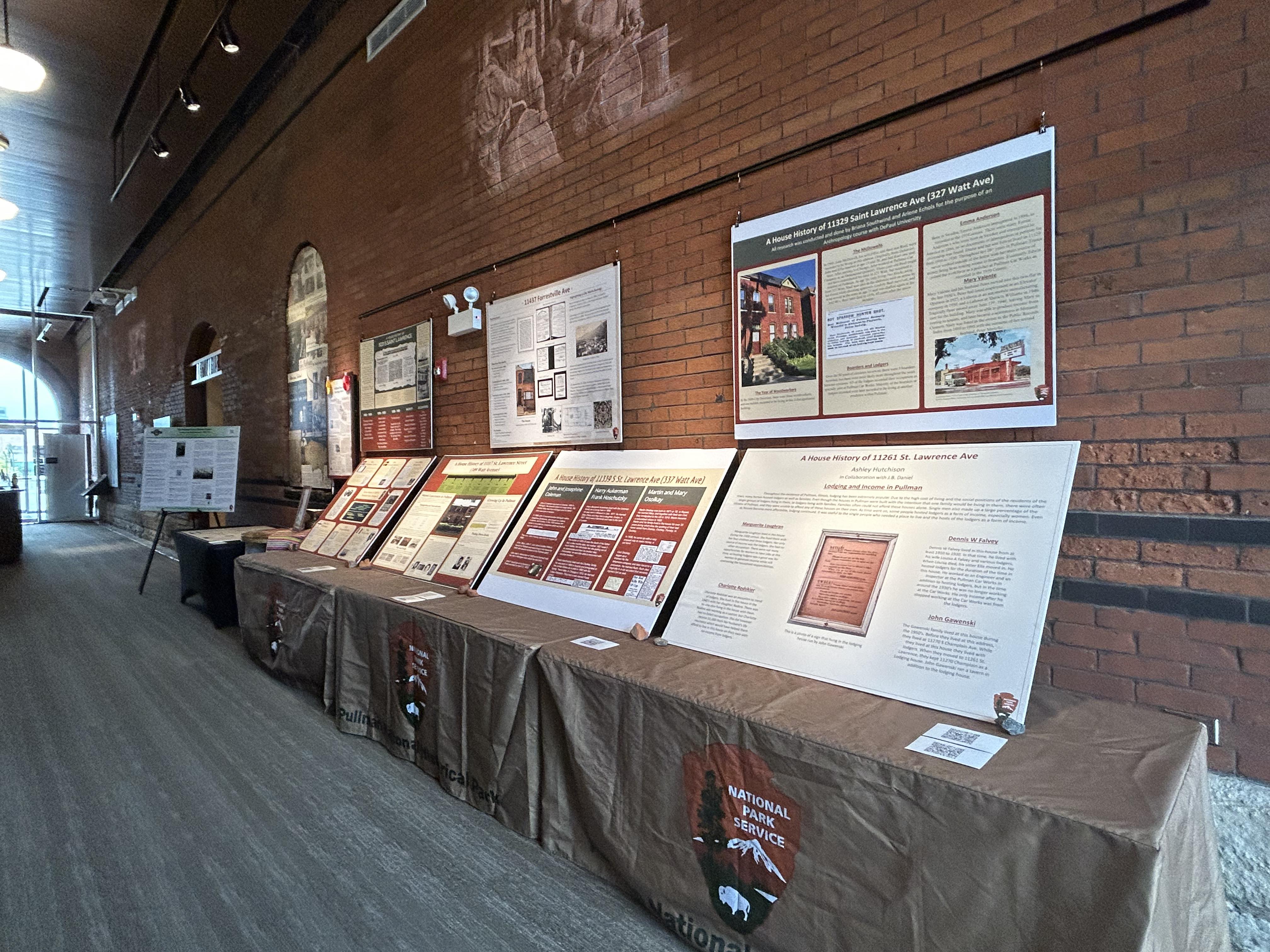

Jane Baxter (left), associate professor and chair of anthropology in the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, stands with Lisa Burbeck, a National Park Service ranger who was also a community participant in the course, and Andy Bullen, Baxter's Historic Pullman Foundation community partner, on exhibition installation day at the Pullman National Historic Park visitor's center. (Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

(Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

(Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

(Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

(Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

(Photo courtesy of Jane Baxter)

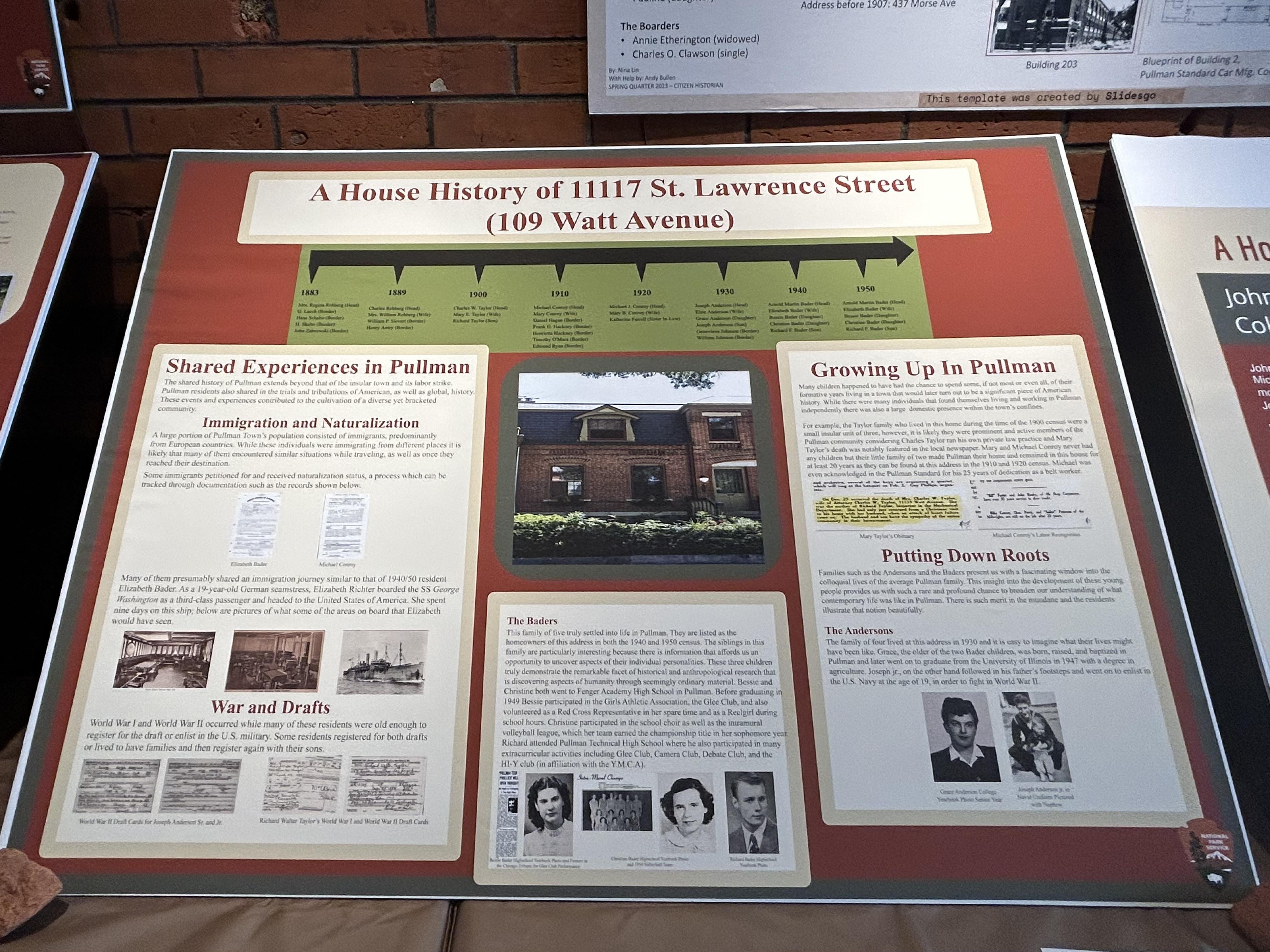

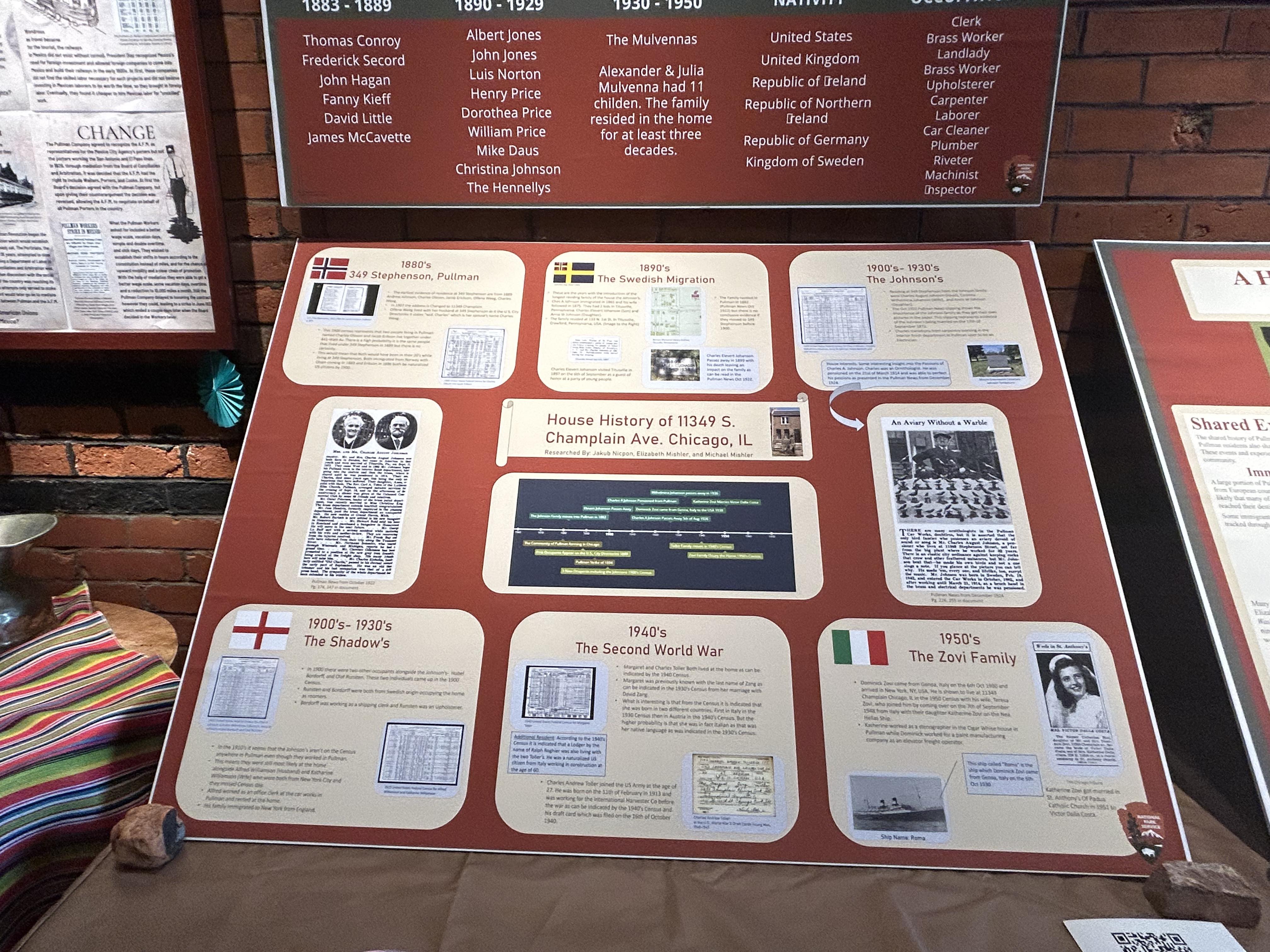

Chicago’s historic Pullman neighborhood was built in the 1880s as a planned industrial community. Now, it is famed for its urban design and architecture and is

Chicago’s only National Park. Over the course of 140 years, families have come and gone from Pullman homes, while celebrating events like birthdays, promotions and weddings.

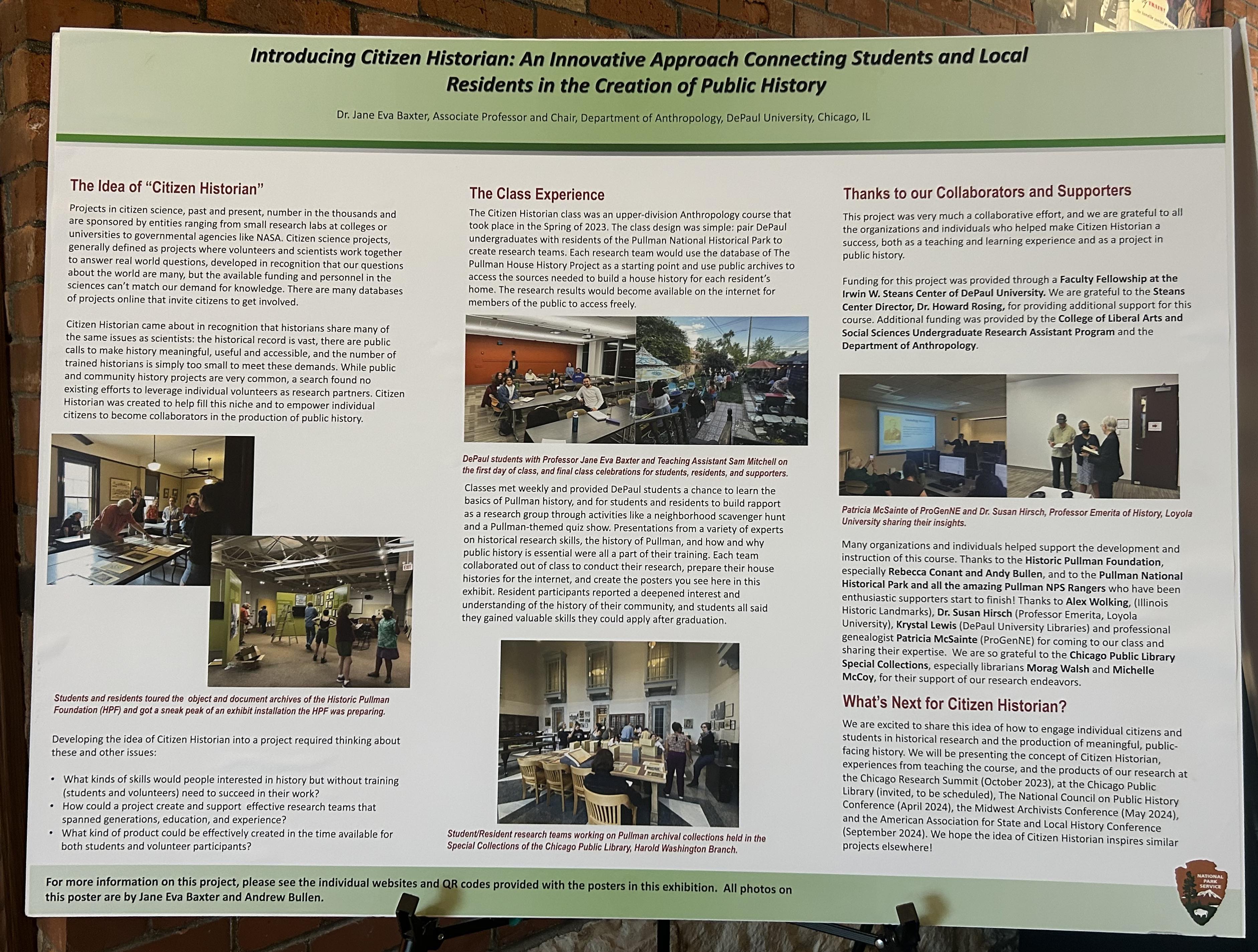

“There’s so much history buried in archives that we would love to know more about, but we don’t have enough historians,” says Jane Baxter, associate professor and chair of anthropology in the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences. “For this project, I challenged our DePaul students to become citizen historians and uncover local, house-level history in the Pullman neighborhood. And the results were amazing.”

With the help of a

Steans Center Fellowship, Baxter paired students in her “Anthropology 390: Citizen Historians” course with a Pullman neighborhood resident who was interested in learning more about their home’s history, beginning with the first residents in the 1880s. Researchers followed the homes through

1950, which is the latest batch of census data available for public viewing, with the 1960 data not coming available until 2032.

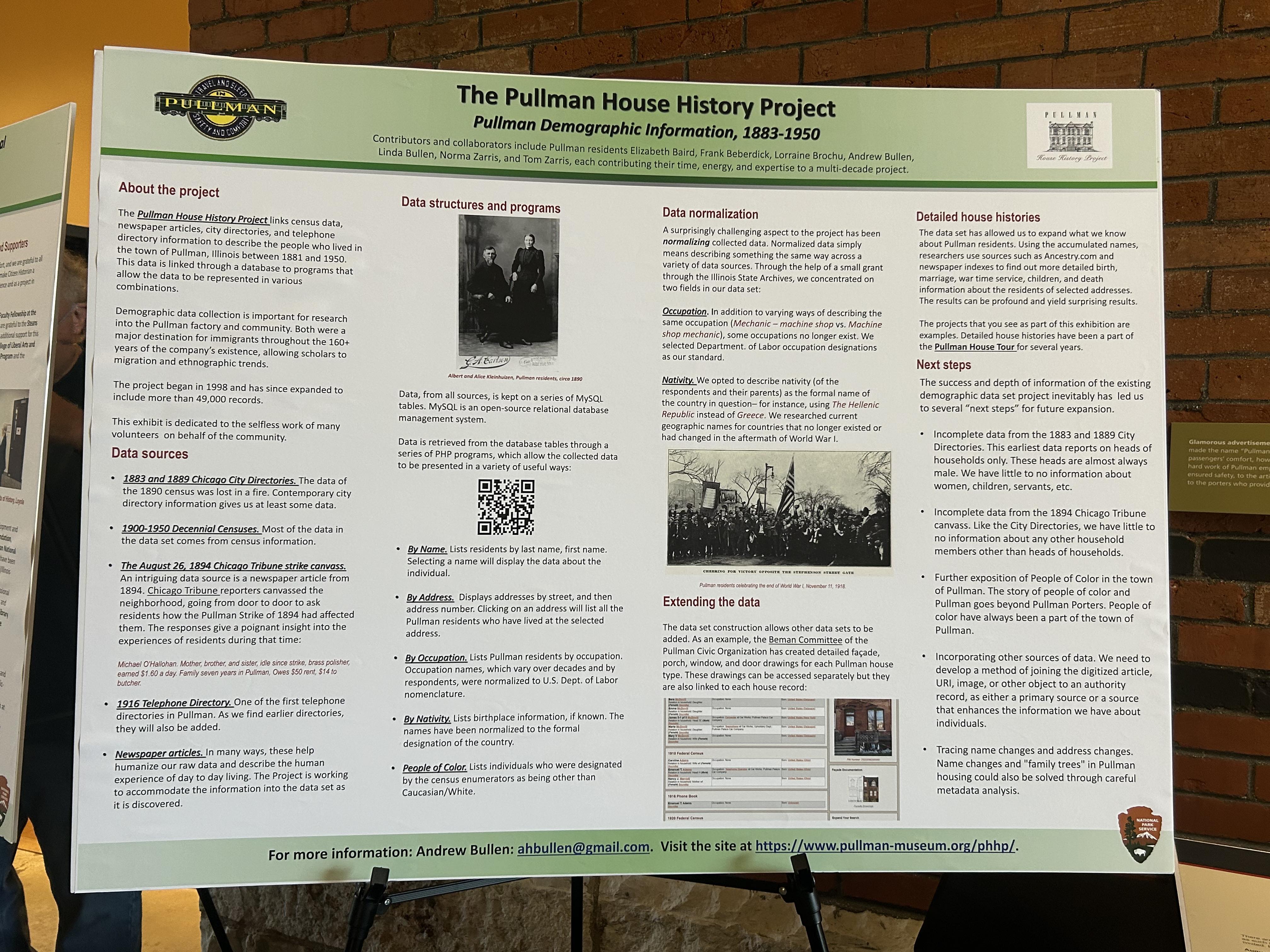

To gather the history, students and their Pullman resident partner poured through historical archives at the Newberry Library and Chicago Public Library, reviewed census data and looked at historic Chicago city directories. DePaul’s students also leveraged their access to Ancestry.com and archives from newspapers and online publications, including the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Defender.

Samuel Mitchell, a senior anthropology major, served as Baxter’s teaching and research assistant for the course.

“Working with the census data was quite interesting because it offered a unique window into both the times and these people's lives,” Mitchell says. “People came from all over the country and world, from Nevada to Connecticut, Greece to Lithuania, and Ireland to Italy. The people worked a number of jobs, from working at the factory to being a ‘dice girl’ or an accordion instructor.”

Some homes were run by single mothers, some by large families, Mitchell found. While some houses had one nuclear family, others had several generations living there and others were boarding houses.

“Vibrant stories and wonderful diversity were written all over the data, a vibrance and diversity that still thrives in Pullman to this day. To be able to experience and uncover that history was amazing,” Mitchell adds.

For Baxter, it brought ordinary history to life for students. “Just because a life seems sort of historically dull, doesn’t mean that’s it’s not meaningful, beautiful and interesting. I think it humanized history for the students and gave them an appreciation for the importance of daily life and the ordinary history that surrounds us,” she says.

Expanding the project beyond Pullman

Baxter and her husband Jim Dourney lived in Pullman for six years and were eager to have their house be part of the project. Dourney paired with a DePaul student to uncover the history of their home and found that families of Irish, German and Scandinavian descent had all lived in their home at one point.

One cool find was that during a previous construction project in their basement, plumbers found some children’s toys that Baxter (an archaeologist by training) dated to the 1930s. When Dourney joined the DePaul class project, he and his DePaul student partner found that two children, Joseph and Grace Anderson, lived in the house during that time. Their best guess is that it was probably the two children who snuck those toys — and some of their mom’s cosmetic jars — under the basement floor.

“Historical research like this is hugely important to the community, especially in the sense of preservation,” Dourney says. “People who have an understanding and connection to the history of a building, neighborhood or community are much more likely to work towards preserving them.”

“We believe this model can be scaled to any historical neighborhood or house in the country,” Baxter says. “It’s a project that can get historical sources out of a dusty archive and put in a meaningful context where people can see them and use them. In my opinion, that’s really the goal of public history.”

Russell Dorn is a manager of news and integrated content in University Communications.