The ship Eltanin sailing Antarctic waters in 1965. McWhinnie called the region the ‘coldest, windiest, most inhospitable place on Earth.’ (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

Mary Alice McWhinnie and crew aboard the Eltanin in 1965. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

Mary Alice McWhinnie conducting research with Sr. Mary Odile Cahoon and Dennis Schenborn in 1974. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

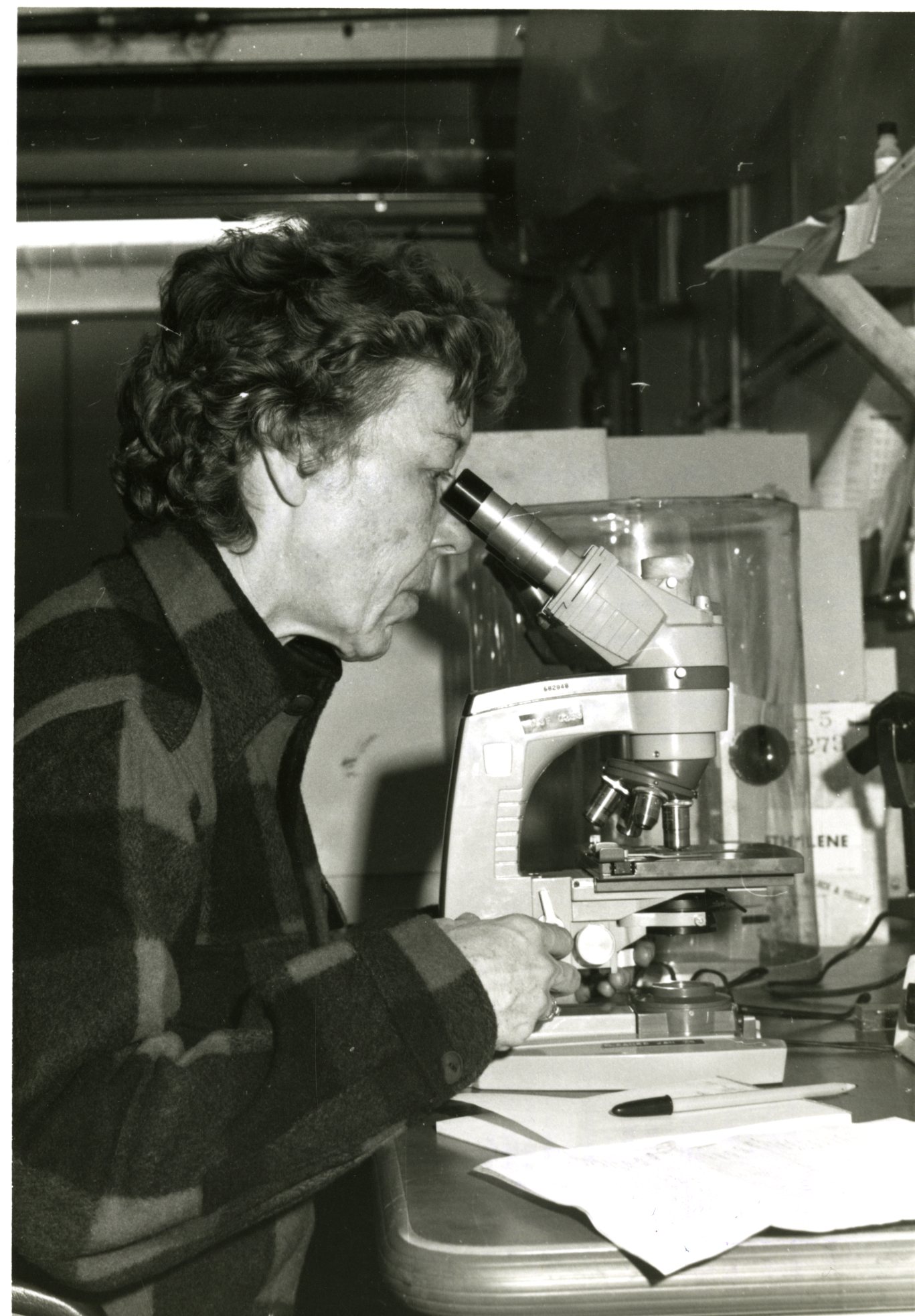

McWhinnie at McMurdo Research Station in 1974. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

When Christie Klimas was growing up, she dreamed of being a researcher in Antarctica. These dreams seemed more attainable thanks to the efforts of scientists like Mary Alice McWhinnie, a Double Demon and long-time DePaul faculty member in biological sciences who became the first woman to sail Antarctic waters.

“Dr. Mary Alice McWhinnie pushed the boundaries of science in extreme environments,” says Klimas, associate professor of environmental science. “Her efforts opened a path for other women to follow. As a scientist who has benefitted from women mentors in science, I can attest to how important it is to have leaders who light the way for those who come after them.”

In 1962, McWhinnie was the first female scientist selected to join the United States Antarctic Research Program and to work with the National Science Foundation aboard the research vessel, the Eltanin. McWhinnie invited Phyllis Marciniak, another woman and DePaul graduate, to be her research assistant for the trip. Her scientific studies focused on the physiology of krill, a shrimp-like crustacean that inhabits Antarctic waters. She published more than 50 articles in scientific journals based on her findings from research trips.

DePaul Special Collections and Archives holds the

Mary Alice McWhinnie papers, which contain correspondence, photographs, press coverage, scientific papers and more. In addition, Dennis Schenborn (B.S. ’74), a former student of McWhinnie’s and member of her 1974 research team, donated the

Dennis Schenborn Collection on Antarctica, which contains photographs, notes, and communications documenting their scientific work and daily life in Antarctica.

In letters to her family and friends, McWhinnie details the difficulties of Antarctic expeditions, including the remote and harsh climate and cumbersome logistics aboard oceanographic research ships. In one letter from 1978, McWhinnie described the conditions aboard her research ship: “I was soaked to the skin and damn near frozen—quiet seas my foot—we were trawling for 7 hrs in sea force 5 (all stops at 8) and, as I was sorting animals, we went awash—me included.”

Mary Alice McWhinnie circa 1970. She made 11 research trips to Antarctica and was professor and chair of DePaul’s Biological Sciences Department in the 1960s. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

Mary Alice McWhinnie circa 1970. She made 11 research trips to Antarctica and was professor and chair of DePaul’s Biological Sciences Department in the 1960s. (Image courtesy of Special Collections and Archives) McWhinnie earned her B.S. (’44) and M.S. (’46) in biology from DePaul. She joined the faculty of DePaul's Department of Biological Sciences as a graduate assistant and became an instructor. After receiving her Ph.D. in Zoology/Physiology from Northwestern University in 1952, she continued to rise through the ranks at DePaul, from instructor to professor in the Biological Sciences Department, chairing the department from 1964-1969.

During her years at DePaul, the university’s faculty was still male-dominated and most department chairs were Vincentian priests. McWhinnie helped advance opportunities for women at DePaul during her leadership of the Biological Sciences Department by hiring women faculty members and serving on the University Promotions Board. She also had a strong research agenda and led efforts to promote faculty research, secure federal funding and to develop Ph.D. programs at DePaul.

The legacy of these efforts lives on. On a modern-day trip to Antarctica, biological sciences faculty member Jalene LaMontagne reflected on the challenges early explorers faced while traveling without seeing land for days.

“I do a lot of field work in other places in my own research,” says LaMontagne, associate professor of ecology. “I’m so impressed by McWhinnie and what she accomplished, from her important research contributions, to the logistics of Antarctic fieldwork, on top of being the only woman on the scientific research team.” LaMontagne conducts research on population ecology in North American white spruce forests. And while Klimas hasn’t been to Antarctica yet, she has traveled to the Amazon and other locations in Central and South America for her own research.

In all, McWhinnie made 11 research trips to Antarctica, most of them aboard the Eltanin with her students. During the 1972 trip, she earned the status of Chief Scientist and two years later, McWhinnie and Sr. Mary Odile Cahoon became the first women to spend the entire winter, from April to October, on the Antarctic continent at the McMurdo Research Station.

McWhinnie’s dedication to DePaul, her work, and her students and colleagues are evident in these archival collections. In 1980, she was posthumously awarded DePaul’s highest honor, the Via Sapientiae Award, for her contributions to the university.

In her letters, McWhinnie displays characteristic tenacity and wit as a pioneering woman scientist. She signed off one of her 1974 letters as, “the girl in the bunny-boots, wind-blown and fishing through 8 feet of sea-ice—at the bottom of the world—the highest, coldest, windiest, most inhospitable place on Earth—Antarctica.”