Public health officials have struggled to collect race and ethnicity data with COVID-19 tests. Data scientists at DePaul created a mobile app to help the City of Chicago fill in the gaps. (iStock.com/bodnarchuk)

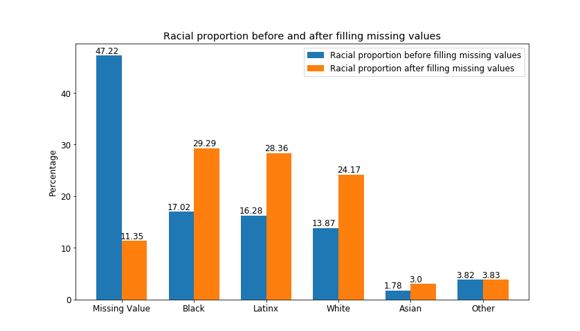

Public health officials have struggled to collect race and ethnicity data with COVID-19 tests. Data scientists at DePaul created a mobile app to help the City of Chicago fill in the gaps. (iStock.com/bodnarchuk)Thousands of people are being tested for COVID-19 each day, but collecting complete demographic information, including race and ethnicity, has proven difficult. Data science researchers at DePaul University have stepped up in Chicago to help public health officials fill in this missing information. Their work imputing data — replacing missing information with predicted values — brought down the category of “unknown” race in COVID-19 tests in Chicago from 47% to 11%.

“This information is essential for understanding inequities with COVID-19,” says Fernando De Maio, professor of sociology and founding co-director of the Center for Community Health Equity at DePaul. Whether individuals are not reporting this information or clinicians are not collecting it, De Maio says this has been a local and national issue since the onset of the pandemic. “Everyone is struggling with missing data, but from what is already available, we know that the burden has been carried in disproportionate ways by minoritized and marginalized communities” De Maio says.

Missing data deepens inequity

When the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) put out a call for assistance with this problem in April, faculty in DePaul’s College of Computing and Digital Media volunteered to help. Data science professor Daniela Stan Raicu and her research team at the Center for Data Science used an algorithm to analyze U.S. census data and available demographic information. They are able to predict an individual in Chicago’s race and ethnicity with 81% accuracy, according to Raicu. The team also developed a mobile application that allows city officials to easily and securely input the data with missing values. “This was our way to help during the pandemic,” says Raicu, who also serves as associate provost for research at DePaul.

The results of DePaul’s data imputation process provided public health officials with “a more complete understanding of the impact of racial inequities within the COVID-19 epidemic in Chicago,” says Margarita Reina, a senior epidemiologist at the Chicago Department of Public Health. “By filling in the missing race/ethnicity data of those testing for COVID-19, CDPH and the city’s Racial Equity Rapid Response Team will be able to better pinpoint and prioritize testing, PPE distribution, community education and stakeholder engagement in our overall COVID response. This was not strictly an epidemiological exercise,” Reina says.

Deep racial segregation in Chicago neighborhoods is part of what made the predictive analytics possible, explained De Maio. “We had someone’s last name and we had the address of their residence. With just those two pieces of information, we can predict their race and ethnicity with a very high degree of accuracy,” De Maio says.

Collaboration closes gaps

DePaul’s Center for Data Science director Raicu recruited graduate students Hao Wu and Yiyang Wang to work with the data. Faculty member Ilyas Ustun, a professional lecturer in DePaul’s School of Computing, worked closely with them to develop an application that would make it easy for public health officials to input daily totals. The researchers used the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding method to predict patients’ unreported racial information based on their surname and geocoding. “As a data scientist, I have been working in medical informatics and biology, but not public health. This was a way for me to take my research in a new direction,” Raicu says.

“People around the world are talking about COVID-19,” says Wang, a third year Ph.D. student in the School of Computing. “An as international student, it’s has been a great opportunity to work on an important project and make presentations. It’s been good practice for us.” Wu echoed that this gave him a chance to work on “real-world” topics, when many others saw internships cancelled over the summer.

DePaul University researchers are helping public health officials fill in missing racial demographic data for those being tested for COVID-19. They used the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding method to predict patients’ unreported racial information based on their surname and geocoding. Their algorithm reduced the missing category of race from 47.22% to 11.35%. (Image courtesy of Daniela Stan Raicu)

DePaul University researchers are helping public health officials fill in missing racial demographic data for those being tested for COVID-19. They used the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding method to predict patients’ unreported racial information based on their surname and geocoding. Their algorithm reduced the missing category of race from 47.22% to 11.35%. (Image courtesy of Daniela Stan Raicu)

First, the team tested their algorithm for accuracy by using data for which the race and ethnicity of an individual was known. For the second part of validation, Ustun connected with researcher C. Scott Smith of DePaul’s Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development. “We worked together to see how sensitive the model was at various geographic scales,” says Smith, assistant director of the Chaddick Institute.

Then it was time to hand the app over to public health officials and make sure it worked for them.

“City epidemiologists and public health officials know the zip codes very well, and could confirm that the process made sense. The collaboration also led to conversations about how this new information could change what we know about how the virus is moving through the city,” Smith says.

New directions in research

As an expert in urban studies and geographic information systems, Smith’s research had largely focused on transportation and urban planning. He has found the pivot to assisting with public health research during the pandemic to be rewarding.

“The pandemic is affecting many different sectors and facets of our lives, including urban planning. We now see that transportation has played a key role in coronavirus-related health outcomes, from access to testing facilities to how urban design impacts probabilities of transmission. That's something we're looking at now,” Smith says.

Looking ahead, the researchers are seeking ways to expand the application so it can be used in other cities. So far, DePaul has done this work with seed funding from its College of Computing and Digital Media.

“We’re happy to help and it’s good that we can, but it’s also a sign of our nation’s under-funded public health system,” De Maio says. “And while we at DePaul have come up with a very practical solution, it doesn't fix the underlying problem. We need to do a better job of funding critical public health infrastructure. And we need to do more to make sure that equity-focused data analysis is always a priority,” he says.

Researchers will present on this and other topics at the Nov. 6 Health Equity and Social Justice Conference, presented by DePaul University’s Master of Public Health Program and the Center for Community Health Equity. The conference is free and will be held on Zoom this year. In its 13th year, the conference aims to bring together community voices, share best practices, and provide a forum for organizations in the Chicagoland area to engage in lively, solution-oriented discussions at a time when many of are separated by remote work. Learn more and RSVP at

http://bit.ly/hesj2020.