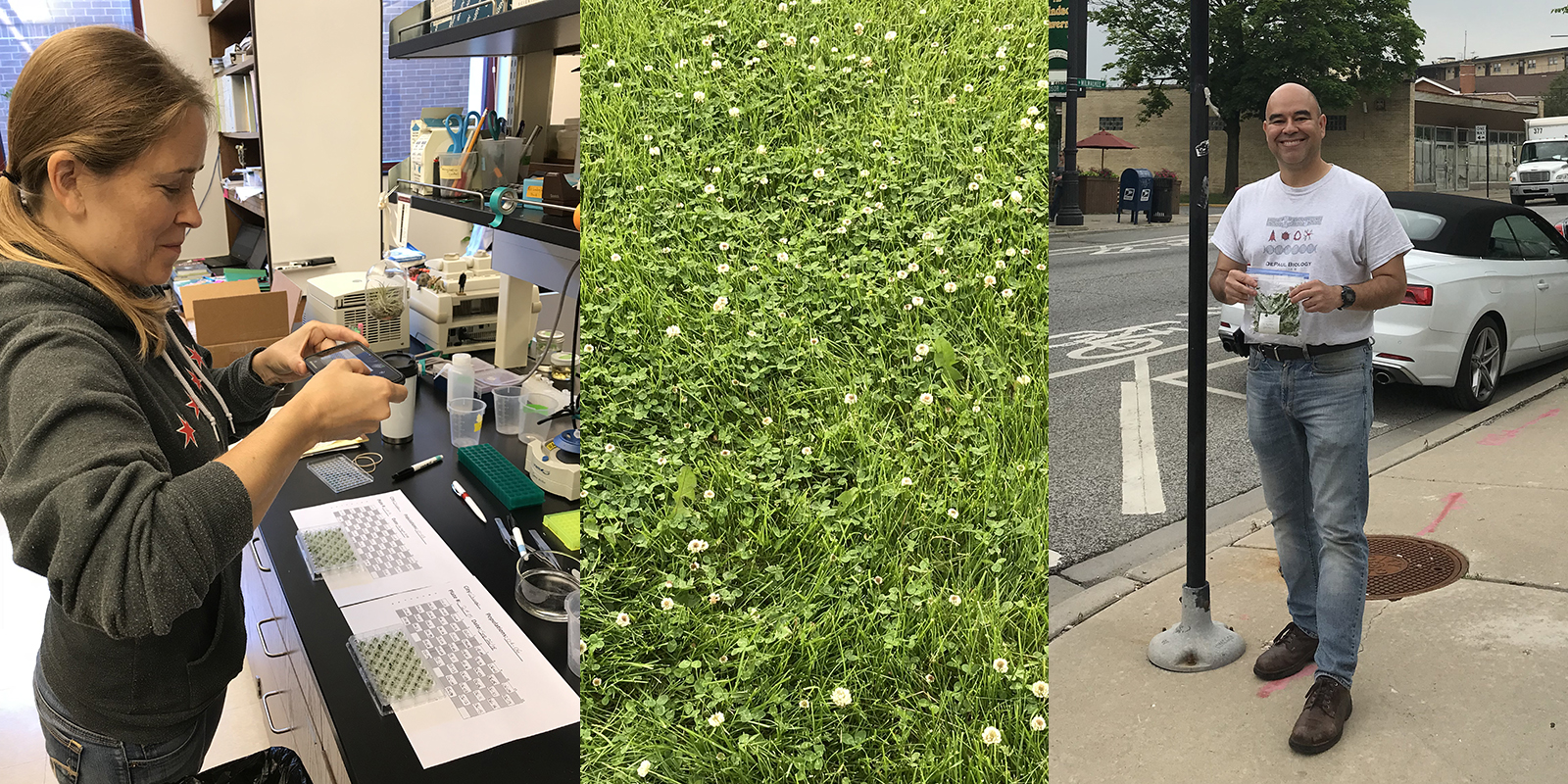

Biological sciences faculty Jalene LaMontagne and Windsor Aguirre are among researchers who collected white clover in 160 cities throughout the world. The resulting study examines how urbanization is transforming the genetic properties of plants. (Images courtesy of Windsor Aguirre)

Biological sciences faculty Jalene LaMontagne and Windsor Aguirre are among researchers who collected white clover in 160 cities throughout the world. The resulting study examines how urbanization is transforming the genetic properties of plants. (Images courtesy of Windsor Aguirre)On a sunny day in 2018, two DePaul biological sciences faculty members spent hours picking clover in parkways and fields across Chicagoland. Humans have spread white clover—the same species that occasionally yields a lucky four-leafed shamrock—into ecosystems throughout the planet. This made it the perfect plant to study for researchers who are interested in taking a global look at how humans are pushing plants to evolve.

Jalene LaMontagne, associate professor of ecology, and Windsor Aguirre, associate professor of evolutionary biology, are among hundreds of researchers who collected clover in 160 cities all over the world. The research, published this week in the journal “Science,” offers insight into how urbanization is transforming the genetic properties of plants and animals around us.

In this Q&A, LaMontagne and Aguirre discuss how clovers gathered from a 50-mile stretch near Chicago are helping to illustrate the global human impact on nature.

Tell us about this research. What changes were you looking for in clover in the city versus in rural areas?

Windsor Aguirre: This was a massive effort, led by researchers at the University of Toronto Mississauga, to look across the globe to see how rural environmental conditions can affect a particular species. The advantage of this species, white clover, is that it occurs everywhere.

In this study, we measured production of hydrogen cyanide, which clover produces as a defense against herbivores. Scientists wanted to know if there was a common pattern of change to the production of this compound when you go from an urban to a rural environment. And the answer is yes. The research shows that natural selection and adaptation are changing the genetic structure of this species in urban versus rural habitats.

Jalene LaMontagne: We designed the sampling and traveled along a 50-mile (80-km) transect, moving from a densely populated area west of the Loop, out to where there were farm fields and horses. We ended the transect fairly close to the Illinois-Wisconsin border.

The results indicate that clover closer to urban areas, including Chicago, lost the ability to produce the toxin hydrogen cyanide, likely because urban areas have fewer herbivores. In the paper, the researchers explore the idea of convergent evolution: Populations in very different areas evolving to have the same traits and characteristics. This is selection that has occurred over a really long time, and the pattern is fairly consistent.

What is groundbreaking about this research, and what does it signal about the impact of humans on nature?

Aguirre: This is one of the largest studies of its kind, examining a global landscape and showing a commonality to how things change. I do research in Ecuador, and there was clover collected there as well from other cities in South America, Asia, Africa and Europe for this study.

LaMontagne: Global change biology is an emerging field, and it includes research on climate change plus topics like this. Urbanization is increasing at unprecedented rates and creating selection pressures by changing the environment. White clover does very well in many different environments, yet we're still seeing changes in its properties in urban areas. We also need to think about changes happening to species that are much more restricted to certain environmental conditions. When this type of selection is happening, species will not be able to cope with shifts in their environment. There are certainly some winners and losers.

Aguirre: I’m an evolutionary biologist, and our students are becoming keen not just about climate change but about broader ways humans are modifying the planet. If organisms are changing their genetic properties to respond to humans, we may look at how to preserve them and their ability to persist among predators or parasites. It can be easy to lose the sense of basic reality that we are organic beings. We are dependent on the planet for natural resources, and there is a real threat about the long-term viability of the planet.

What will happen next with this research? How can you envision bringing it into the classroom?

Aguirre: There was a big advantage to using a common species. I teach classes with labs and would like to have students sequence the genes and look for the variants in this local species.

We often think of biologists going to very exotic places for research. And while both Jalene and I enjoy traveling to do research, it’s nice to show really cool examples of evolution in everyday organisms adapting around us.

###

Sources:Jalene LaMontagne

Windsor Aguirre