(helovi/iStock)

(helovi/iStock)With the “

Napoleon” film recently released in theaters, some moviegoers may want to learn more about the historic main character. Fortunately, DePaul

Special Collections and Archives contains the second largest Napoleon Bonaparte collection in the United States, with over 4,000 documents. Over the years, DePaul students have translated some of the documents into English.

Collecting a large archive

According to Jamie Nelson, head of Special Collections and Archives, an online exhibition of the collection detailed how DePaul obtained 4,000 documents from the family of Otto Lempke, a Milwaukee native who created a large personal library due to his interest and admiration of Napoleon, after his passing in 1937. The collection grew in 1984, when 221 books and broadsides, including extra-illustrated editions, were donated to DePaul. Estate gifts and transfers from other institutions contributed objects such as ceramic figurines, engraved hand-bound books and English language novelty publications to DePaul’s collection.

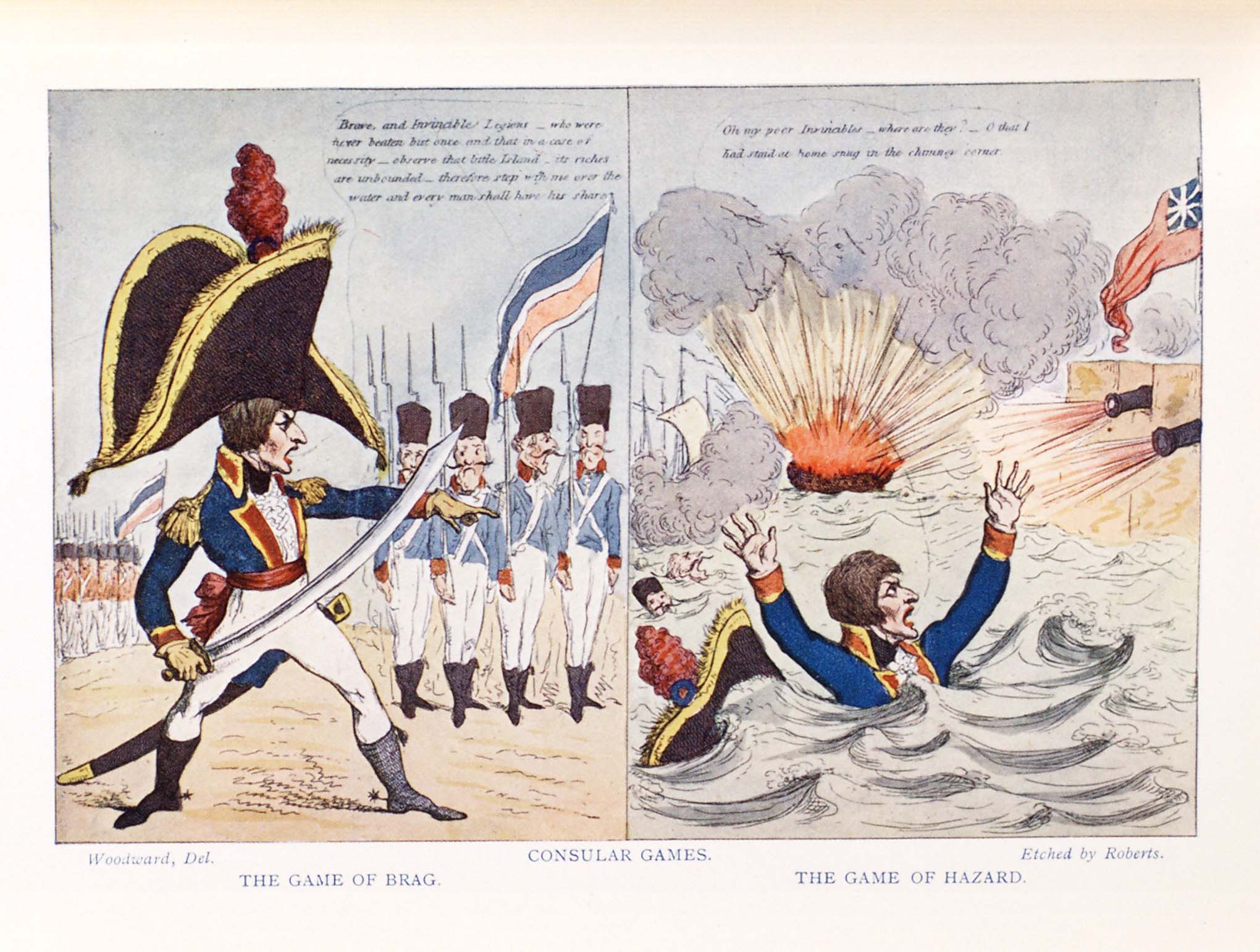

One of the some 4,000 Napoleon items in DePaul Special Collections and Archives titled "Napoleon in Caricature 1795-1821." (Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)

One of the some 4,000 Napoleon items in DePaul Special Collections and Archives titled "Napoleon in Caricature 1795-1821." (Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives)DePaul’s Napoleon collection has also been featured in two

additional exhibitions focusing on the

Battle of Waterloo. According to Nelson, DePaul recently worked on a project to fill in gaps from various sources, including the National Library of France’s Digital Library, The Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, the Internet Archive, Hathi Trust and Google Books. “When we did the project, DePaul made specific pamphlets and broadsides available that the European libraries did not own, or had not

digitized,” Nelson says.

This

wealth of resources, although many documents were written in French and German, can be accessed through DePaul Library’s Special Collections and Archives.

A resource for French scholars

Pascale-Anne Brault, professor and director of the French program, showcased some of the documents as part of three upper-level French translation courses between 2002 and 2011. Students were paired to translate various documents, including “The Testament from Empress Josephine” and a treatise on why “Napoleon did not die of cancer.” They added introductions and footnotes for context.

According to the Napoleon project website created during these courses, “Each translation went through many drafts and benefited from collective class critiques. From researching the period, to familiarizing themselves with the language of the time, to reaching out to historians, the medical community and other specialists, students went to great lengths to make sure that their translations were as faithful as possible to the originals.”

The students’ translations can be read online through the project website and are available to the public. According to Brault, they have proved useful to many.

“I noticed that there have been some 16,000 downloads of these documents since they were translated, indicating that there is still a strong interest in Napoleon's legacy,” Brault says. “In addition to these downloads, other Napoleon scholars — such as Peter Hicks, from the Napoleon Foundation in Paris, and Tom Vance, author of “Napoleon in America”— have visited DePaul to make use of the collection,” she adds.

The

Napoleon project website explains that “the hope is that [the translations] might prove helpful to history students and general readers, many of whom might not have the linguistic skills to do research in French but could still be interested in the content of these documents.”

Through the sheer number of sources, as well as the students’ translations, DePaul’s Napoleonic collection encapsulates history waiting to be explored.

Jade Walker is a student assistant of media relations and communications in University Communications.