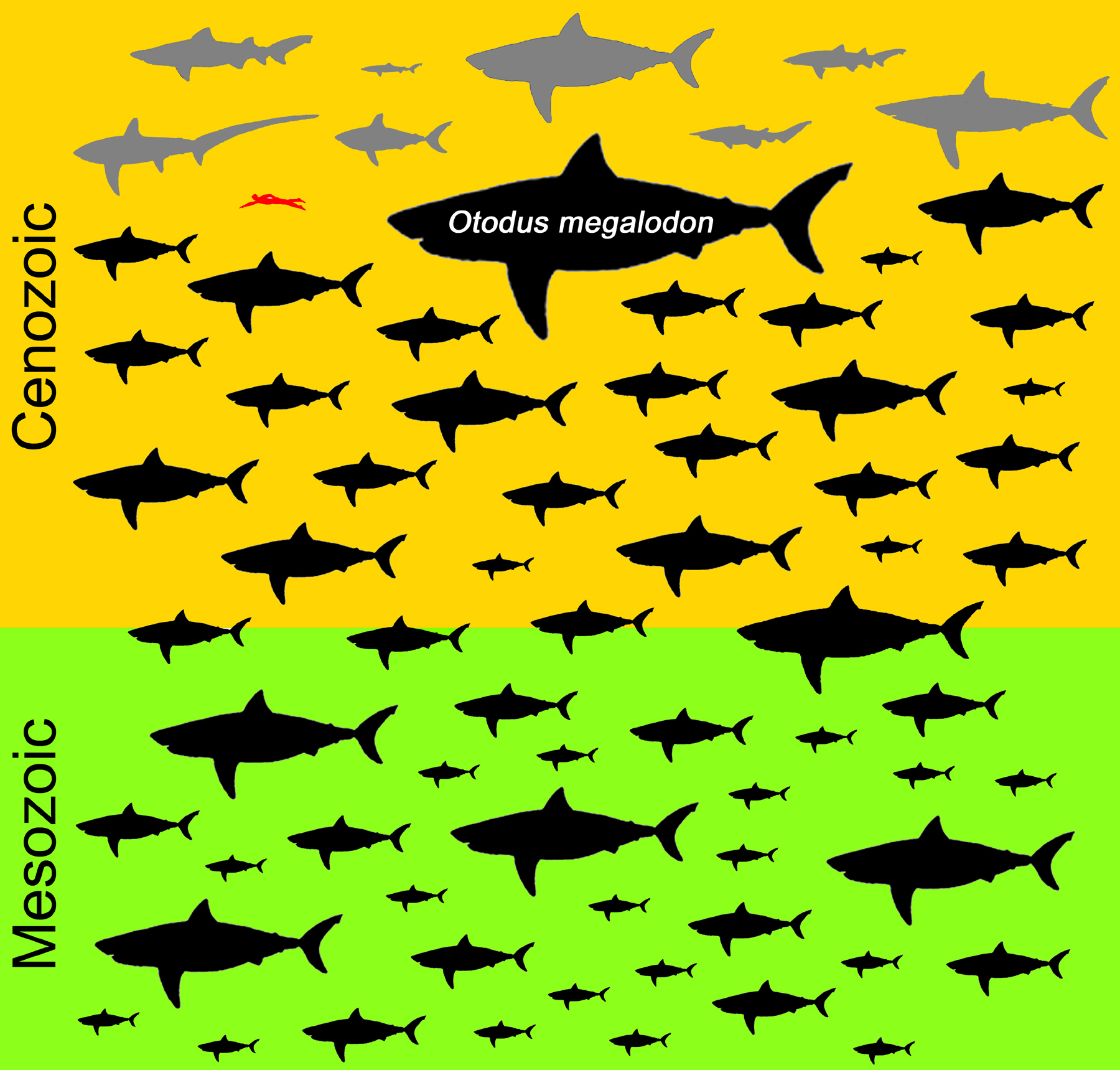

Schematic drawing showing the distribution of maximum possible sizes of all known 70 non-planktivorous genera (groups) in the shark order Lamniformes, comprising modern (in gray) and extinct (in black; with hypothetical silhouettes) members and in comparison with an average adult human (in red) as scale. It is important to note the anomalously large size of the iconic megatooth shark,

Otodus megalodon (50 feet, or 15 meters), and the fact that the Cenozoic Era (after the age of dinosaurs, including today) saw more lamniform genera attaining larger body sizes than the Mesozoic Era (age of dinosaurs). (DePaul University/Kenshu Shimada)

Schematic drawing showing the distribution of maximum possible sizes of all known 70 non-planktivorous genera (groups) in the shark order Lamniformes, comprising modern (in gray) and extinct (in black; with hypothetical silhouettes) members and in comparison with an average adult human (in red) as scale. It is important to note the anomalously large size of the iconic megatooth shark,

Otodus megalodon (50 feet, or 15 meters), and the fact that the Cenozoic Era (after the age of dinosaurs, including today) saw more lamniform genera attaining larger body sizes than the Mesozoic Era (age of dinosaurs). (DePaul University/Kenshu Shimada)A new study shows that the body size of the iconic gigantic Megalodon or megatooth shark, about 50 feet in length, is indeed anomalously large compared to body sizes of its relatives. Formally called

Otodus megalodon, the fossil shark that lived nearly worldwide roughly 15-3.6 million years ago is receiving a renewed look at the significance of its body size in the shark world, based on a new study appearing in the international journal "Historical Biology."

Otodus megalodon is commonly portrayed as a super-sized, monstrous shark, in novels and films such as the 2018 sci-fi thriller “The Meg.” However, experts know the scientifically justifiable maximum possible body size for the species is about 50 feet at present, or 15 meters; not 16 meters or larger in some previous studies. Nonetheless, it is still an impressively large shark, and the new study illuminates exactly how gigantic the shark was relative to other sharks, notes Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist in the College of Science and Health and lead author of the study.

Otodus megalodon belongs to the shark group called lamniforms with a rich fossil record, but the biology of extinct forms is poorly understood because these cartilaginous fishes are mostly known only from their teeth. The study used measurements taken from specimens of all 13 species of present-day macrophagous (non-planktivorous) lamniforms to generate functions that allow estimations of body, jaw and dentition lengths of extinct macrophagous lamniforms. These quantitative functions enabled the researchers to examine the body size distribution of all known macrophagous lamniform genera over geologic time.

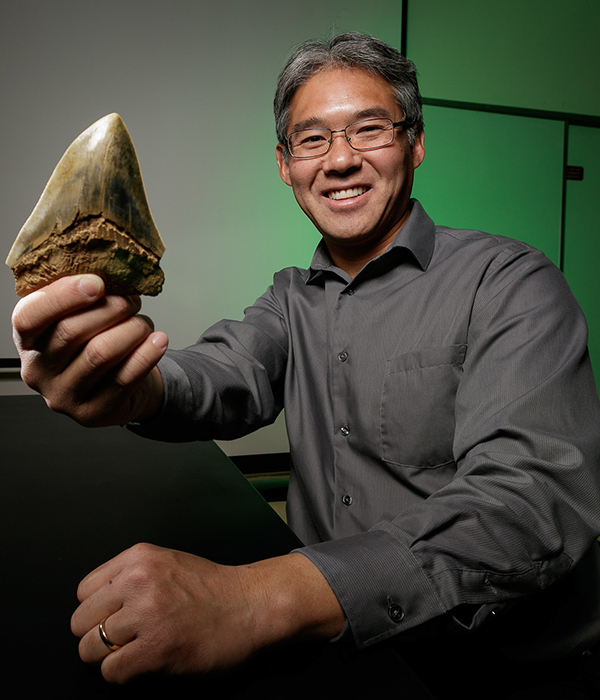

DePaul paleobiologist Kenshu Shimada holds a tooth of an extinct shark Otodus megalodon, or the so-called “Meg” or megatooth shark. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

DePaul paleobiologist Kenshu Shimada holds a tooth of an extinct shark Otodus megalodon, or the so-called “Meg” or megatooth shark. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

The study demonstrates

O. megalodon reaching at least 46 feet is truly an outlier. Practically all other macrophagous sharks, including extinct forms, have a general size limit of 23 feet. Only a few plankton-eating sharks, such as the whale shark and basking shark, were equivalent or came close to the size. The study also reveals that the Cenozoic Era (after the age of dinosaurs, including today) saw more lamniform lineages attaining larger sizes than the Mesozoic Era (age of dinosaurs).

Warm-bloodedness has previously been proposed to have led to the gigantism (20 feet) in multiple lamniform lineages. The new study proposes a live-bearing reproductive strategy with a cannibalistic egg-eating behavior nourished early-hatched embryos to large sizes inside their mother to be another possible cause for the evolution of gigantism in lamniform sharks.

“This is compelling evidence for the truly exceptional size of megalodon,” notes co-author Michael Griffiths, a professor of environmental science at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey.

Understanding body sizes of extinct organisms is important in the context of ecology and evolution.

“Lamniform sharks have represented major carnivores in oceans since the age of dinosaurs. It is reasonable to assert they must have played an important role in shaping the marine ecosystems we know today,” Shimada says.

Another co-author of the study, Martin Becker, a professor of environmental science at William Paterson University, notes this work's importance.

“This study represents a critical advancement in our understanding of the evolution of this ocean giant," he adds.

The new study, "Body, jaw, and dentition lengths of macrophagous lamniform sharks, and body size evolution in Lamniformes with special reference to ‘off-the-scale’ gigantism of the megatooth shark,

Otodus megalodon,” will appear in the forthcoming issue of "Historical Biology" and is

available online.

This study is based on work supported in part by a National Science Foundation Sedimentary Geology and Paleobiology Award to Shimada (Award Number 1830858) as well as to Michael Griffiths and Martin Becker of William Paterson University (Award Number 1830581).