Min. Jené Colvin, Leyfane Thomas, Stephen Haymes, Vicky Privert and Valerie Johnson gather at Aspasia LeCompte Hall. (Photos by Jeff Carrion/DePaul University)

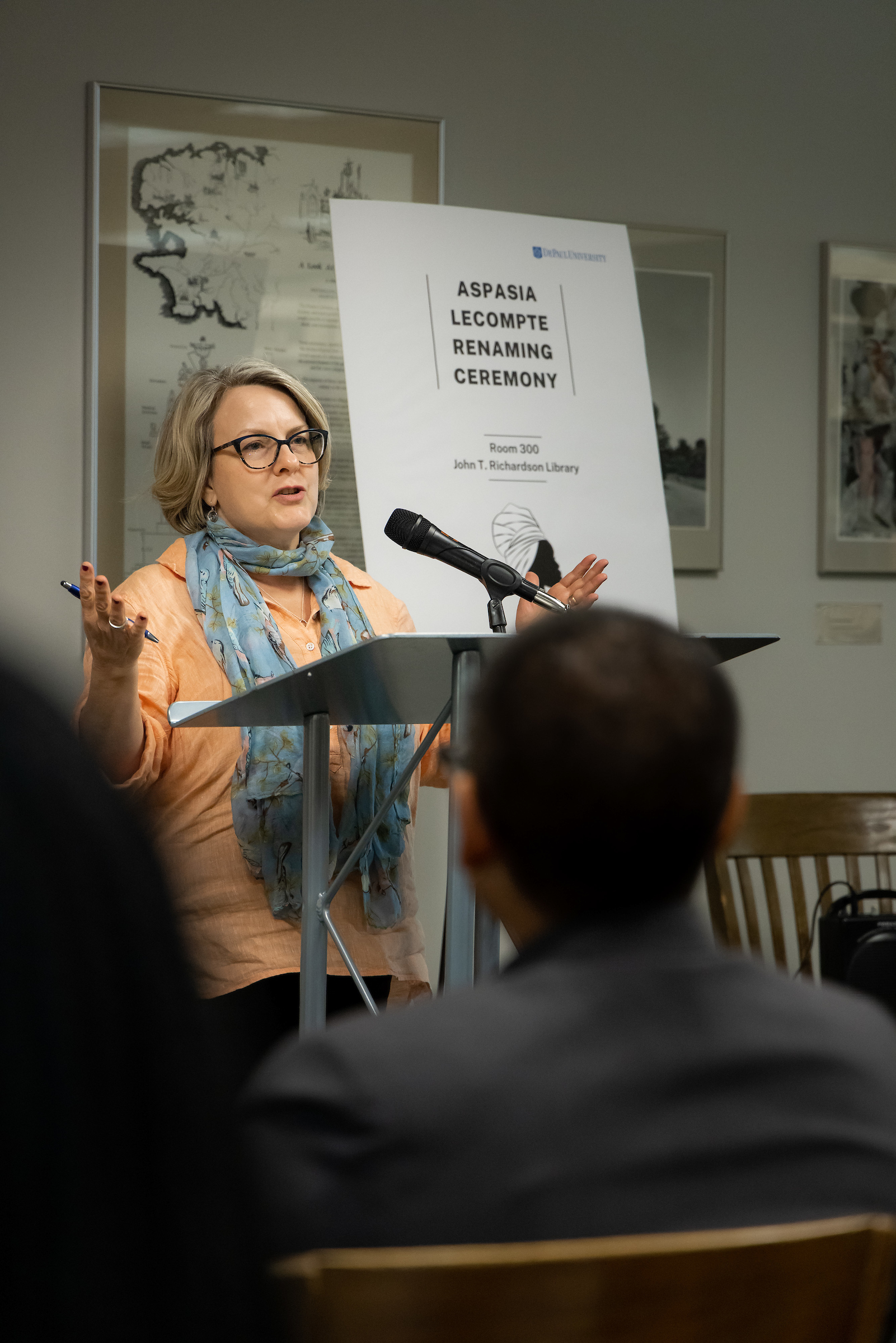

Provost Salma Ghanem delivers remarks at the John T. Richardson Library.

Lori Pierce describes the task force's historical research.

Margaret Storey describes the task force's historical research.

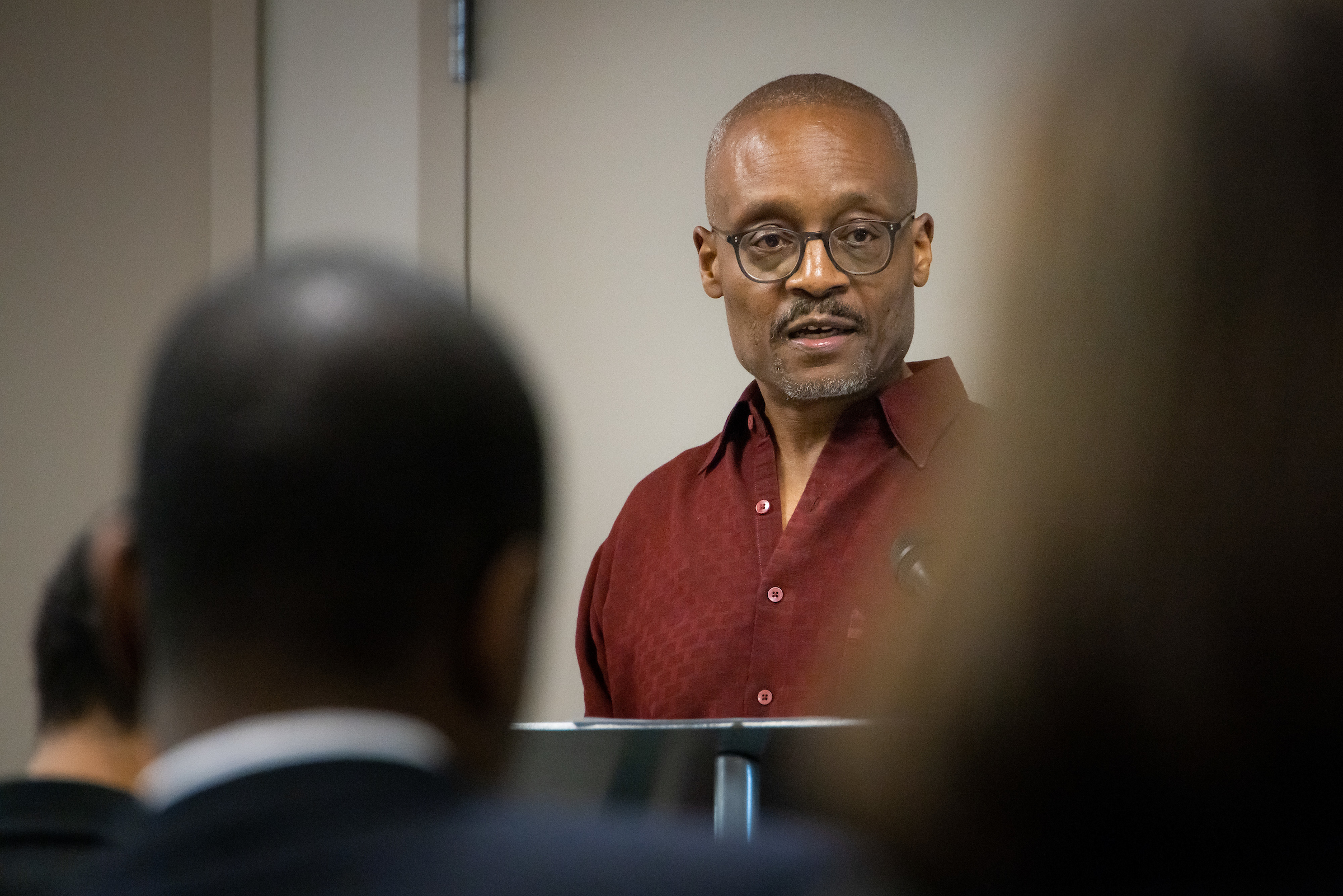

Stephen Haymes, an associate professor in the College of Education, delivers remarks.

Shajuan Young unveils the Aspasia LeCompte room in the library. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Students Angela Rojas and Angela Hernandez perform at the ceremony.

Attendees walk in silence to the residence hall.

Those gathered listen to remarks outside the residence hall.

Sign is unveiled at Aspasia LeCompte residence hall.

Aspasia LeCompte and her family were held in bondage by Vincentian priests in Missouri in the early 19th century. Through determination, solidarity and use of the courts, LeCompte and five of her family members obtained their freedom. Bishop Joseph Rosati, C.M., one of the founders of the Vincentian Mission in the United States, was one of the Vincentians who enslaved LeCompte.

On May 18, DePaul University gathered for the renaming of two campus spaces in LeCompte's honor: Room 300 in the John T. Richardson Library and the Belden-Racine residence hall. The event was the culmination of more than two years of research and work by faculty and staff on the task force to address the Vincentians' relationship with slavery. The task force also unveiled

a new website, where visitors can learn more about this history.

Provost Salma Ghanem recognized the many emotions of those present, from sadness to humility. She also expressed hope and gratitude for the task force and their work: "I am excited that a Black woman is becoming central to our collective ethos and the naming of campus spaces, in honor of her fight, her struggle, her resilience and her victory to become free and to help free others."

Members of the task force also spoke during the event. Lori Pierce, associate professor in the Department of African and Black Diaspora Studies, and Margaret Storey, professor of history and associate dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, shared how they uncovered the history of Vincentian slaveholding.

Pierce reminded the audience that it can be a daunting task to recover pieces of the past from a record incomplete because information was lost, destroyed or never recorded in the first place. In the case of the Vincentians, the record was there, but having the proof is only one small part.

"We have to commit the time and gain the institutional support for the task of recovery," Pierce said. "That way, we can do the copying and scanning, interpreting, writing and storytelling over and over again until it sticks to the present and is secured for the future."

Storey described the lived experience of the people enslaved by the Vincentians in Missouri in the 1800s.

In Missouri, the slave holdings were smaller than in the deep South, and enslaved people could be hired out to others, worked on farms or in homes or engaged in various types of skilled labor. The Vincentians practiced this kind of slaveholding. "This does not necessarily make slavery 'better' or less severe. It just means the dynamic was slightly different," Storey said.

Because the Catholic Church cared about the sacramental lives of the people they held in bondage, they kept marriage, baptism, death and, importantly, financial records.

"The financial records are what we spent most of our time looking at in the archives, here, right down the hall," Storey said. "It's through the little scraps of this record keeping that we've managed to build up a sense of who some of the [enslaved people] were and the lives they led."

Valerie Johnson, associate professor of political science and interim associate provost of diversity, equity and inclusion, spoke about the incredible character and will of Aspasia LeCompte.

"She actually, quite literally, embodied our mission and, in fact, better than those who promulgated the mission," Johnson says.

She noted that LeCompte began her quest for her freedom in 1827, based on Missouri law known as "once free, always free." LeCompte persisted for 12 years through appeals and multiple owners, one of whom was Bishop Rosati, before she finally won her freedom in 1839.

"She [fought] for her own freedom and the freedom of her family, and she will certainly be enshrined in history as a freedom fighter," Johnson said. Her family members became free in 1844.

Stephen Haymes, associate professor in the College of Education, shared some history between Black Catholics and the Church. Early on, the church used slaveholding to expand new dioceses across the United States. Catholic leaders sold enslaved people to relieve debts related to expansion and funded religious orders with wealth generated by people in slavery.

"There was general acceptance of slavery, even among Catholics who were not slaveholders," Haymes said.

In the aftermath of slavery, newly freed individuals gathered and formed their own Black Catholic churches, segregated from white congregations, which became spaces where they were allowed to worship without facing prejudice and discrimination.

To end the library portion of the ceremony, Fr. Memo Campuzano, C.M., vice president of Mission and Ministry, invited the audience to walk to the LeCompte residence hall (formerly Belden-Racine residence hall) in silent reflection.

"We are walking elbow to elbow as the greatest advocates of the civil rights movement [did] in many, many streets and bridges of this country. Ours is a very humble memory of their conviction, passion and determination. Ours is a remembrance of our own commitment, so that the march for civil rights and freedom is never finished," Campuzano concluded.