A

new scientific study provides many new insights into the biology of the prehistoric gigantic shark, Megalodon or megatooth shark, which lived nearly worldwide 15-3.6 million years ago. Paleobiology professor

Kenshu Shimada of DePaul University’s Departments of Environmental Sciences and Studies and Biological Sciences, led the study along with 28 other shark, fossil, and vertebrate anatomy experts around the globe.

The research team also included two of Shimada’s former master’s students and DePaul University alumni, Phillip Sternes and Jake Wood. Highlights of the study include:

- The team examined as many living and fossil shark groups as possible, which is a brand-new approach to estimating the size of the prehistoric shark.

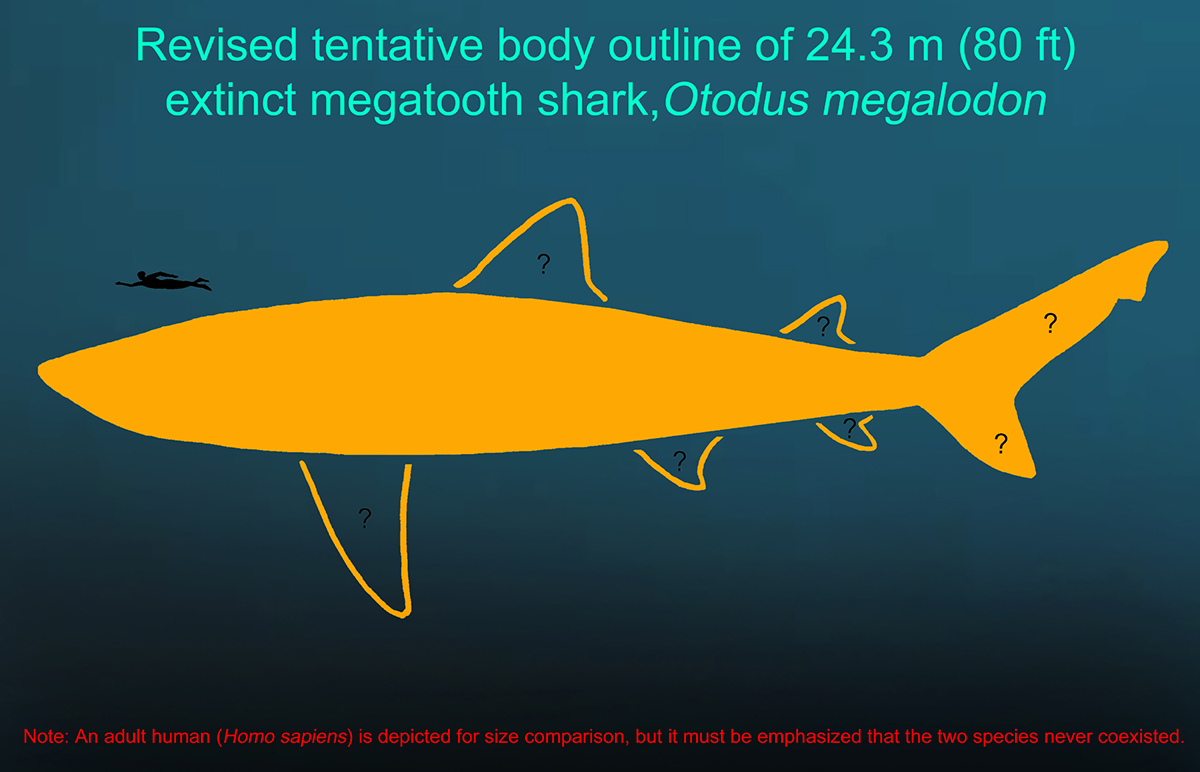

- They determined that the largest, reasonable length estimate of the prehistoric shark is 80 feet.

- They also determined that the shark was most likely slender, because large marine vertebrates with stocky bodies cannot be efficient swimmers.

- Large, stocky sharks, like the great white, cannot grow to gigantic proportions because of ‘hydrodynamic constraints.’

The specimen and research question

A nearly complete, fossilized trunk vertebrae of O. megalodon measuring about 36 feet in length in Belgium has been well-researched, but the new study asked a question that has not been asked before: “How long were the parts not represented in the fossil specimen, notably its head and tail lengths?”

To address the question, the team of researchers surveyed the proportions of the head, trunk, and tail relative to the total body length across 145 modern and 20 extinct species of sharks.

“The length of 80 feet is currently the largest possible reasonable estimate for O. megalodon that can be justified based on science and the present fossil record,” Shimada says.

Findings on body shape

Shimada and his team’s study didn’t end there. Based on comparisons of their body part proportions, they determined that the body form of O. megalodon was likely more slender than the modern great white shark.

They also noticed that modern-day gigantic sharks, such as the whale shark and basking shark, as well as many other gigantic aquatic vertebrates like whales, have slender bodies because large stocky bodies are hydrodynamically inefficient for swimming.

What sets this study apart from others?

“Our new study has solidified the idea that O. megalodon was not merely a gigantic version of the modern-day great white shark, supporting

a previous study of ours,” Sternes says, who is now an educator at SeaWorld San Diego.

“What sets our study apart from all previous papers on body size and shape estimates of O. megalodon is the use of a completely new approach that does not rely solely on the modern great white shark,” Wood adds, now a doctoral student at the Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida.

“Many interpretations we made are still tentative, but they are data-driven and will serve as reasonable reference points for future studies on the biology of O. megalodon,” Shimada says, who hopes a complete skeleton would be discovered someday to be able to put the interpretations to test.