At the start of Hispanic Heritage Month, over 100 people packed Cortelyou Commons as DePaul University honored the Young Lords organization and their legacy of battling gentrification and displacement of the Puerto Rican community in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. As part of the event, DePaul previewed a plaque that will commemorate their transformative work.

“For Puerto Ricans in the U.S., an important part of our history is being recognized and memorialized right here on DePaul’s campus,” says Jaqueline Lazú, a Society of Vincent de Paul Professor in the Department of Modern Languages. “Every time we take a step toward uncovering and correcting some of that history, we’re engaging social justice education and inviting everyone in our community to be active agents of change.”

The Sept. 18 event, “¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park,” featured speeches by Omar López, former minister of information for the Young Lords, journalist Juan González, a founding member of the New York City Young Lords, and Melissa Jiménez, daughter of José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, the founder of the Young Lords. Paul Mireles, a DePaul master's student in critical ethnic studies, also shared his experience as chairman of the Chicago Chapter of the New Era Young Lords. Those gathered also enjoyed a performance by musicians La Escuelita Bombera de Corazón, a Puerto Rican Bomba group.

A street gang turned activist organization founded in Lincoln Park, the Young Lords became the largest and most well-known Puerto Rican participants of the Civil Rights Movement. In May 1969, the Young Lords, under the banner of the Poor People’s Coalition, peacefully occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary’s Stone Administration Building at 804 W Belden Ave., which is now owned by DePaul and houses part of the School of Music. Activists argued that the seminary had a moral obligation to care for the poor people and people of color with roots in Lincoln Park, who were actively being displaced by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley’s urban renewal plan.

For Lazú, the marker, which will be located near the School of Music building, is a major step forward in honoring an activist group that played a big role in Chicago during the 1960s and onward.

“My hope is that the marker will spark curiosity in those who read it and compel them to want to learn more about the Young Lords and the history of Lincoln Park. I hope they can appreciate the lessons of solidarity in the movement and continue to discover new things about our history to share with the public,” Lazú says.

The first large wave of Puerto Ricans arrived in Chicago in the 1950s, and they started to settle into the Lincoln Park neighborhood, says Lazú, who is working on two books about the group. One is a comprehensive history about the origins of the movement and the other a volume of primary materials co-edited with members of the original Young Lords.

“The ‘barrio’ of Lincoln Park had developed a strong social fabric with mom-and-pop businesses, restaurants and entertainment before it was uprooted. It was a uniquely diverse neighborhood, especially for the era, and made Lincoln Park an incubator of social movements like the Young Lords,” she says.

Lazú describes the McCormick takeover as successful because the seminary agreed to many of the Young Lords’ terms, such as funds to support healthcare programs that the group had established. They also received a pledge from the seminary to help them establish plans for low-income housing in the community and seed money to establish the People’s Law Office, which is still part of Chicago today.

The Young Lords later took over the Armitage Avenue Church after the congregation repeatedly denied them space in the basement for a community daycare. With the support of the pastor who was an ally of the movement, they renamed it the People’s Church. The space became the group’s national headquarters where they ran the Betances Health Clinic, free daycare and breakfast programs, and a Puerto Rican cultural center.

“The far bigger victory for the Young Lords is the fact that we're still talking about the movement today as something that impacted the imagination and identity of the Puerto Rican diaspora,” Lazú says. “They're still the entryway into political consciousness for many of us. And, you can't talk about the history of Puerto Ricans in the U.S. without talking about the Young Lords of Lincoln Park.”

Russell Dorn is a manager of news and integrated content in University Communications.

The Young Lords occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary's Stone Administration Building in May 1969. (Photo taken by Luis Arevalo and is courtesy of DePaul University Special Collections and Archives.)

The Young Lords occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary's Stone Administration Building in May 1969. (Photo taken by Luis Arevalo and is courtesy of DePaul University Special Collections and Archives.)

The Young Lords occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary's Stone Administration Building in May 1969. (Photo taken by Luis Arevalo and is courtesy of DePaul University Special Collections and Archives.)

The Young Lords occupied the McCormick Theological Seminary's Stone Administration Building in May 1969. (Photo taken by an unknown photographer and is courtesy of DePaul University Special Collections and Archives.)

DePaul President Robert L. Manuel (right) and Jacqueline Lazú (second from right), associate professor of modern languages, chat with José "Cha Cha" Jiménez (left), founder of the Young Lords organization, on Sept. 18, 2023 before "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Jacqueline Lazú, associate professor of modern languages, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Omar López, former Minister of Information for the Young Lords, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Juan González, a journalist and founding member of the New York City branch of the Young Lords, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Paul Mireles, a DePaul master's student in critical ethnic studies and chairman of the Chicago Chapter of the New Era Young Lords, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

Melissa Jiménez, daughter of José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

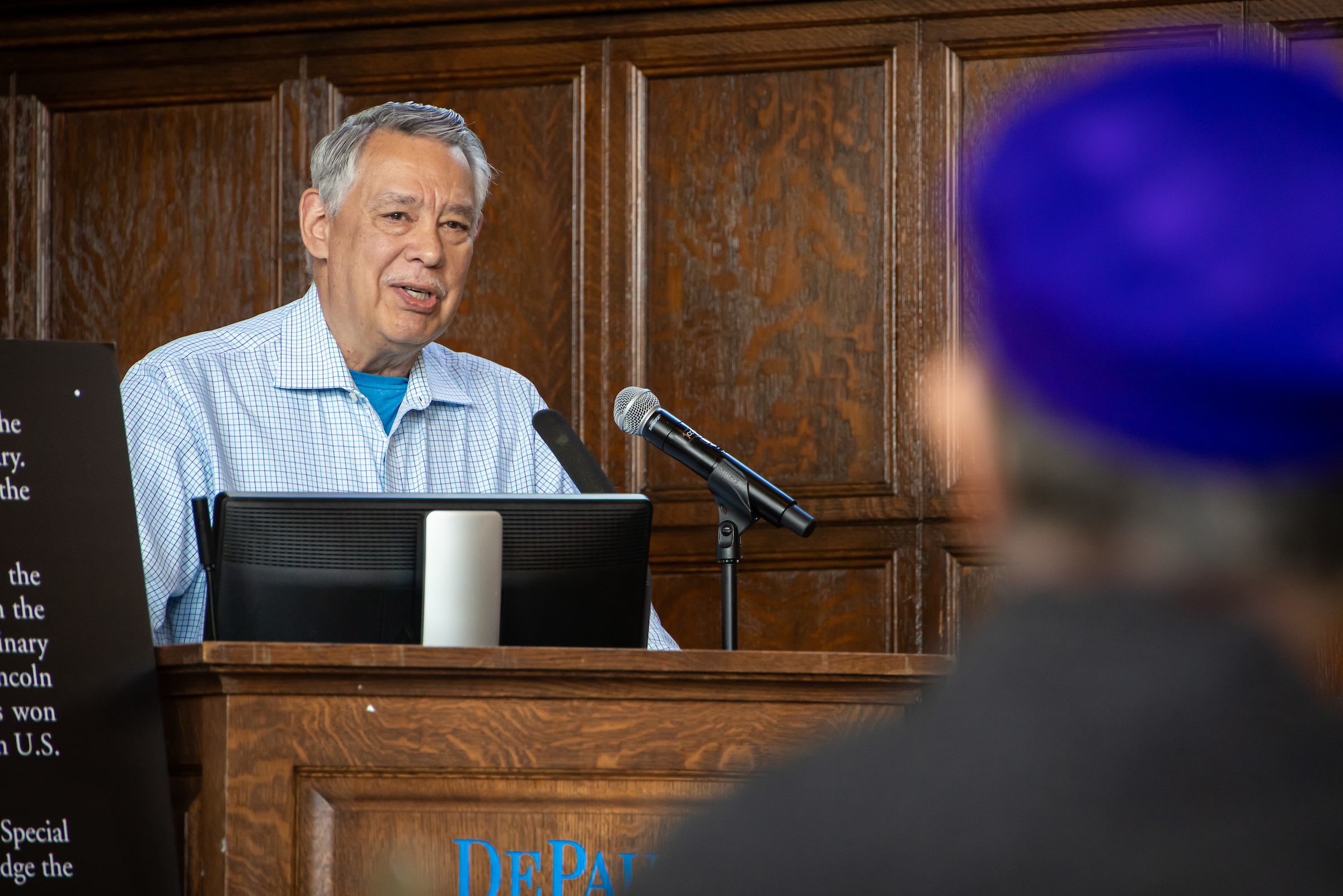

Bill Johnson González, director of DePaul's Center for Latino Research, addresses the crowd in attendance for "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

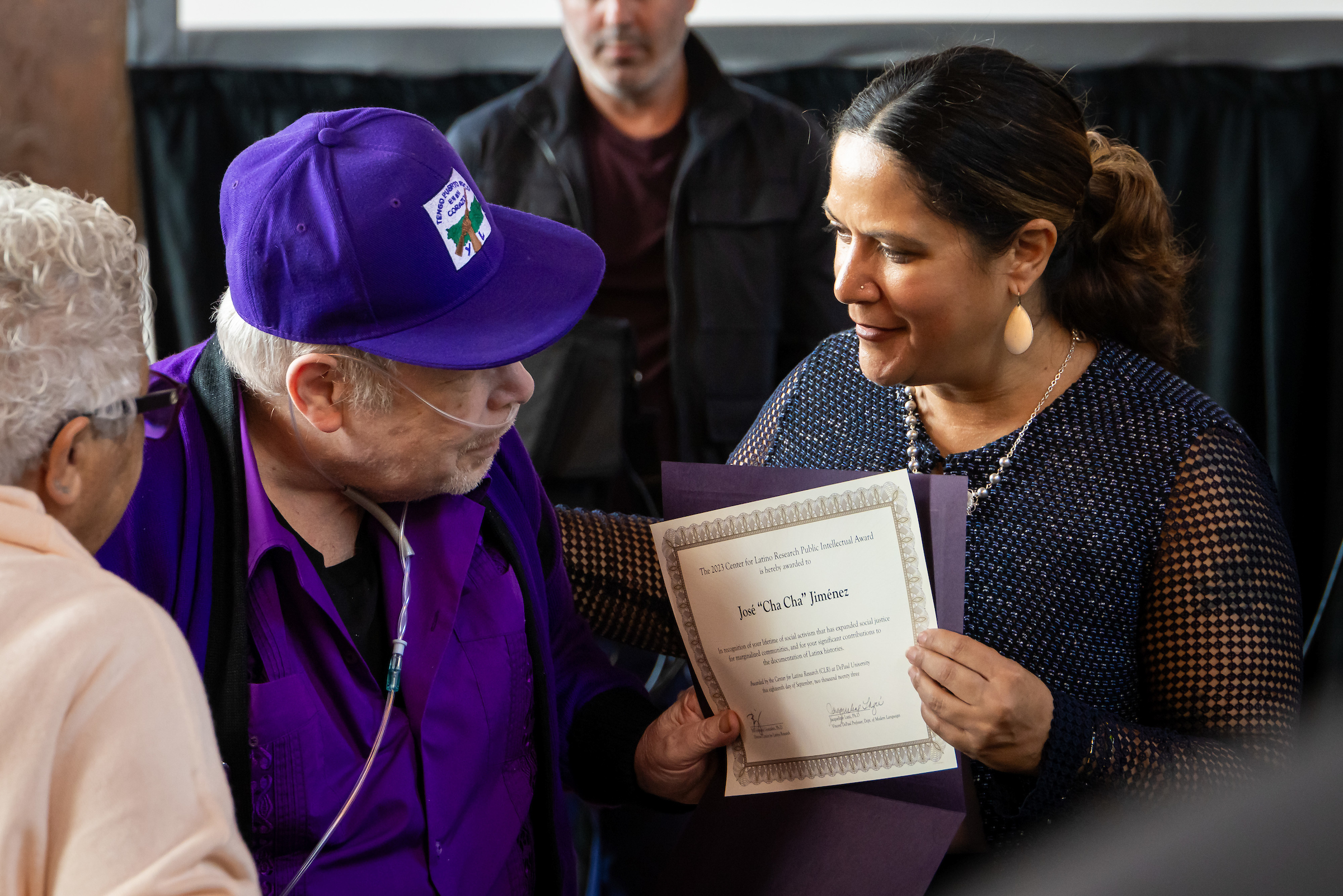

Jacqueline Lazú (right), associate professor of modern languages, presents José "Cha Cha" Jiménez (left), founder of the Young Lords organization, with the 2023 Center for Latino Reseach Public Intellectual Award at the "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" event at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)

La Escuelita Bombera de Corazón, a Puerto Rican Bomba group, performs Sept. 18, 2023 at the "¡Todo el poder pa’ la gente!: 55 Years of Young Lords in Lincoln Park" event at Cortelyou Commons. (DePaul University/Jeff Carrion)