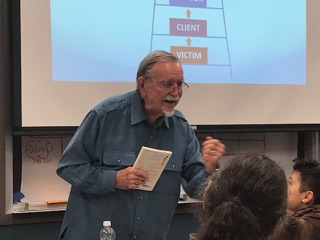

“I think we are already part of a movement to recover the capacity of local residents to become neighbors and citizens so that their lives can be transformed,” says ABCD Institute co-founder and retired Northwestern University professor John McKnight. “It has to come from the people in the community.”

John's own story is about an individual who emerged out of midwestern communities in Ohio to attend Northwestern University and then serve in the Navy in the Korean War. From that point forward, it is hard to capture in a short profile the vast array of work he has accomplished over the many decades since he began community organizing, engaging in activism, teaching and doing research. Over the years, however, his work has been mostly in urban neighborhoods where, along with colleague John Kretzmann, it eventually clicked that there was something missing in the way people in the academy engaged with and understood communities.

For decades, their work has focused on the most essential

– and often overlooked - resource of all: the capacity of individuals in communities to build relationships that lie at the foundation of positive change. “My basic underlying assumption is that when people work together,

their impact can be more powerful than if they are isolated,” he says.

McKnight’s career arc is closely connected with the

history of community organizing in Chicago. Years before ABCD was created, he

was engaged in a range of jobs that focused on key issues impacting communities

in Chicago and around the country. At

the Chicago Commission on Human Relations – the first public civil rights group

in the U.S. – he learned community organizing in the style of legendary

organizer Saul Alinsky, who emphasized the ability and power of people to help

themselves. Later he became director of the Illinois Chapter of the ACLU,

where he organized chapters around the state on issues including police

brutality. He was in charge of

the federal affirmative action program for the Midwest Region. Later, he served as

Midwest Director of the Civil Rights Commission where he worked closely with

community organizations in the city.

The list of highlights from the above experiences is lengthy but one that stands out, he says, was being part of a Chicago Freedom

Movement coalition of groups that invited Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. to the city and held a summit on housing, nondiscriminatory

lending and related issues.

By the end of the 1960s, McKnight and his colleagues began building the infrastructure that would eventually give birth to ABCD as a concept. In 1969, he was invited to help start a new department

at Northwestern, the Center for Urban Affairs, which later became the Institute

for Policy Research. They placed students at neighborhood

organizations to work on projects and it was around this time that he met Jody Kretzmann, who

co-founded the Urban Studies Program at Associated Colleges of the Midwest which was also placing students in neighborhood organizations. After collaborating on research across North America, McKnight

and Kretzmann co-founded the Asset-Based Community Development Institute during the early 1990s.

“We learned,” McKnight says, “that

ABCD is not some magic bullet that solves all problems. It is the

identification of tools or resources that exist in almost all neighborhoods

that people use when they want to make things better. While he speaks about ABCD’s growth from an idea to an

institute with faculty members across the world, he points out that

it’s really about the close-to-the-ground stories of how people in communities use

their assets to improve their lives. One example, he says, is what happened in

Chicago’s West Garfield Park neighborhood. “Mary Nelson is a great example of

how you can turn deficits in a neighborhood into assets,” he says. “She started

a little nonprofit that trained people on how to convert brownfields into

usable land.” Nelson, a faculty member of the ABCD Institute, turned that organization into Bethel New Life, a major institutional community asset that directly reflects the interests of local residents.

Based on what he has seen in his long career, McKnight envisions a specific role for ABCD in the coming years. “The role of ABCD in my mind is to be an inspiration and activator for communities and neighborhoods to be places that carry on major functions that have to do with security, health, education, food, environment and other issues. But people in these communities do that as citizens – they are not trying to get institutions to do it.” To McKnight, to quote his writing the “history of institutions assuming community functions is a major cause of community dysfunction.”

McKnight says, the move to DePaul makes sense because

of the university’s long history of focusing on local communities and its willingness to engagement faculty, staff and students through places like the Steans Center. “It was a natural fit.”