Students in Jessica Pamment’s Introduction to Biology classes

have long been accustom to lectures and labs staple to a course taken by

non-biology majors to fulfill a requirement. For the last couple

of years, they have engaged in something different: an

experience that gives them real-world grounding

in how science can reach young people in under-resourced Chicago communities.

“One of my first questions was ‘How do we integrate service

learning into a biology class?,” asks Pamment. Her course has answered this

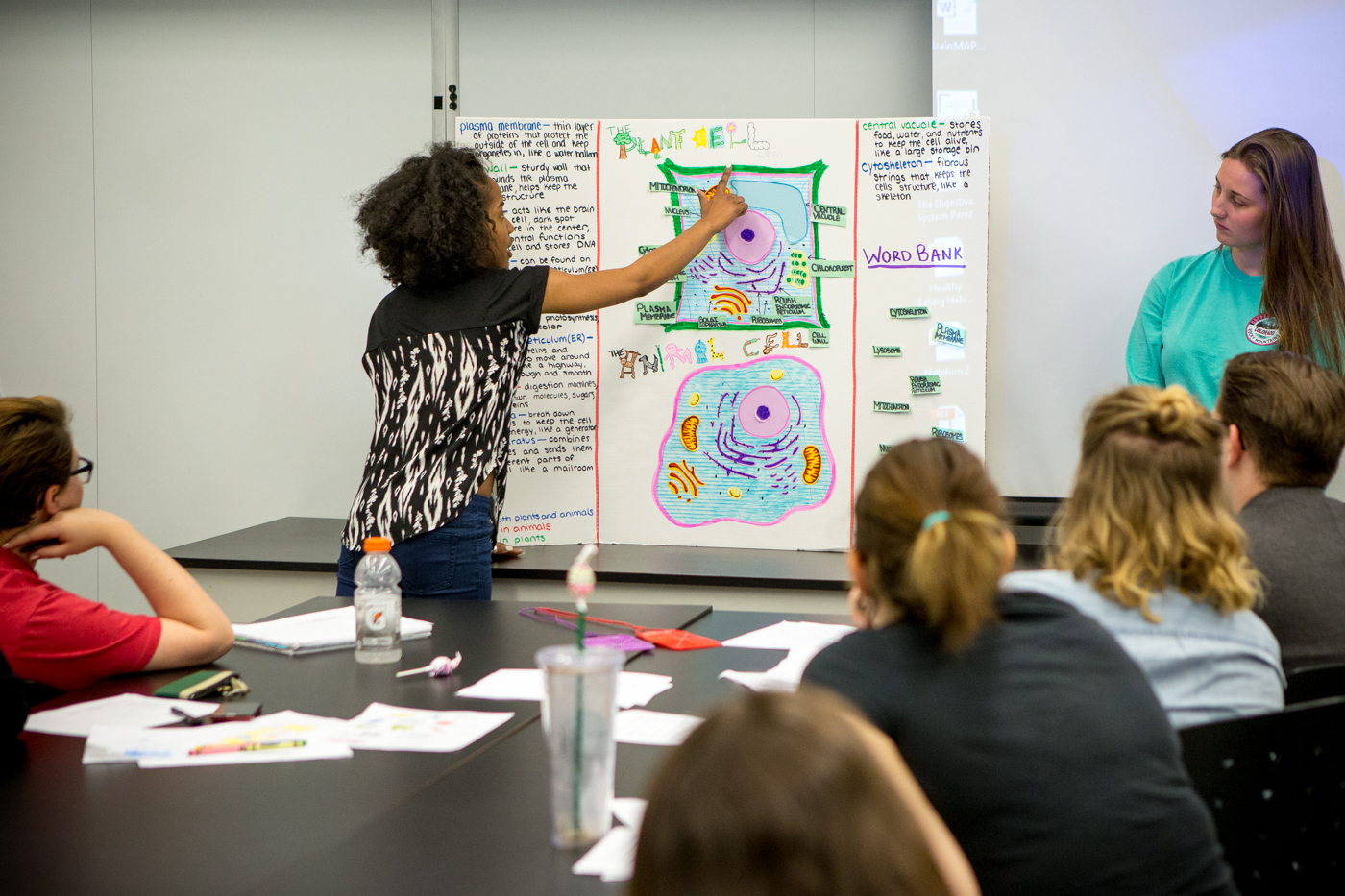

question through a project-based approach that places students in teams to design projects that reach young students at Chicago HOPES for Kids, an organization that provides educational

support for young children living in homeless shelters, as well as

at San Miguel School, a private and independent Catholic school that serves sixth

to eighth graders in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood. The Steans Center partners with San Miguel

and other Catholic schools through its Egan Office for Urban Education and Community Partnerships.

Pamment says she partly assesses students in the course based on evidence

of their preparation, organization, creativity, and how they manage their time in

groups. Her students' projects, centered on how young

students in Chicago communities can benefit from exposure

to STEM education (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math), offer the contexts for achieving these objectives. Helen

Damon-Moore, Associate Director of the Steans Center, says that students in

Pamment’s class “create curriculum for younger students. That makes great sense because many schools are starved for STEM education.” At the same time, students in a biology course for non-majors learn course content through working in teams to design curriculum to teach others about biology, nutrition and science in general.

Professor Jessica Pamment

Professor Jessica Pamment

Pamment

credits the Steans Center with helping her integrate service learning into the

course. “The Steans Center has been amazing – without them there’s no way we

could have done it. They provided a lot of support. The key for this class was

delivering service learning activities without cutting the original content of

the class.”

Emme Veenbaas, a former service learning coordinator at the Steans

Center who was pursuing a master’s in women and gender studies at DePaul, worked

with project-based courses on biology and other subjects. Veenbaas

led reflections with the biology students about their experience and

how it relates to their education. “We really try to drive the point that the

project goes beyond the class,” she says.

“Students are learning great career skills – they have to meet someone

else’s expectations and develop a project. These projects are a great way for

students to be active participants in their learning - and an opportunity to

make an impact in a school.”

Miranda Standberry-Wallace, Academic and Community Service

Learning Coordinator at the Steans Center, says that Pamment’s class is showing

students how their engagement with communities is making a difference. “Students see this is not just a

required course. This kind of course is activating their activism.”

Erin Hempstead, Director of Academic Intervention Programs

at San Miguel School, has worked at the school for ten years and says that

“service learning by DePaul students flips the idea of service. Sometimes

people have this idea of going to an organization and being the person in

power. When DePaul students come to San Miguel it levels the playing field a

little bit – these students and our

students both have things to share and give. We’re really grateful for the

relationship with DePaul, and we’d love to see how it can continue to grow.”

Samuel Mayers-White, a master’s student in school

counseling, works at the Egan

Office and is a site coordinator at San Miguel School through the Catholic

Schools Internship Program. His role includes serving as a liaison between San

Miguel and DePaul as well as other community assets. Mayers-White says the STEM focus of biology students “is in

line with what San Miguel tries to do – make STEM feel accessible to its

students. It’s a real asset to the teachers for DePaul students to provide new

ideas that help teachers present the material and shape it in new ways. I

definitely think service learning could work for other science classes as

well.”

At Chicago HOPES for Kids, Executive Director Patricia

Rivera says part of the process with the class has been recognizing that a

low-tech approach will work better for students than a higher tech approach,

since students don’t have the kind of access to computers that students in many

schools are used to. “I asked them to think more about younger kids –

kindergarten through fifth grade – and then do things where they could move

blocks around or cut things out or have a race. They did a real nice job. The

DePaul students came up with ideas for games, teaching about science, biology

and nutrition.” Rivera has visited the class at DePaul at the start and end of

quarters.

It’s important that people in a school like ours that has access to

resources can do whatever we can to reach out to communities

Jessica Freeman, a sophomore from Springfield who majors in

secondary art education, took the biology class in the fall of 2017. She worked

with a group of four students to make a Jeopardy game that went to San Miguel

students. “We made a slide show and questions for a Jeopardy game that shared

information about nutrition, breaking down what foods do what, and related

subjects. I was surprised by how much I learned, and was encouraged that what I

was learning would be translated to students at San Miguel. A lot of kids don’t

have people telling them about healthy foods.”

Nick Riback, a sophomore from Scottsdale, AZ who is majoring

in political science, developed a presentation that “compared science to pseudoscience.” He

adds that his group’s project focused on “how actual scientific evidence is

linked to factual behavior.” Riback says that his experience in the biology class is as

much about learning as teaching kids through these projects. “We are doing so

much research that we are learning a lot about our topics,” he says.

Nick Riback, a sophomore from Scottsdale, AZ who is majoring

in political science, developed a presentation that “compared science to pseudoscience.” He

adds that his group’s project focused on “how actual scientific evidence is

linked to factual behavior.” Riback says that his experience in the biology class is as

much about learning as teaching kids through these projects. “We are doing so

much research that we are learning a lot about our topics,” he says.

Meanwhile, Matthew Roney, a junior majoring in political

science from Mokena, IL worked on a group project for students at Chicago

HOPES for Kids. His group created a physical board game through which kids

learn about biology and how DNA works. “This service learning project created a

whole new dynamic for students,” he says. “It was great to know that third

through fifth graders can use the game we created as a way to learn about STEM.”

Roney adds that he believes the project “can be replicated at other program

sites – and in other classes as well.”

Christian Flanary, an advertising major who graduated in

June 2018, engaged in a project during the fall of 2017 with

Chicago HOPES for Kids. Like many students in the class, Pamment says, Flanary

was able to utilize his talents gained from the experience. “I made

this rap song about nutrition for the class, and I did it to the tune of a

Biggie Smalls rap,” he said. Flanary’s song included the following lyrics: “All them sugar and fats,

as a matter of fact,/are terrible for your body,/ so it’s time to act/yeah it’s

time to get healthy and active, don’t delay/Thank you for letting me rap today.”

Flanary further noted that “It’s important that people in a school like ours that has access to

resources can do whatever we can to reach out to communities,” he says. “In

doing so, sometimes you have to be creative. That’s why I did it as a rap. It

was lighthearted and fun – but students paid attention.”

“Overall,” Pamment adds, “My students enjoy the course more

because of the service learning component,” she says. “It also improves the

dynamics in the classroom when students work together on projects.” While students take her course for a quarter, her

engagement with Chicago HOPES and San Miguel have become long-term

relationships. “The longer you work with a partner,” she says, “the more value

it has. What if one or two children who are exposed to a DNA model or model of

a cell show an interest in those subjects? What if a child who wouldn’t have

considered going to college sees that they can do that? We have a chance to

expose these kids to new things. Maybe they’ll say ‘Hey, I want to do that.’”

“Overall,” Pamment adds, “My students enjoy the course more

because of the service learning component,” she says. “It also improves the

dynamics in the classroom when students work together on projects.” While students take her course for a quarter, her

engagement with Chicago HOPES and San Miguel have become long-term

relationships. “The longer you work with a partner,” she says, “the more value

it has. What if one or two children who are exposed to a DNA model or model of

a cell show an interest in those subjects? What if a child who wouldn’t have

considered going to college sees that they can do that? We have a chance to

expose these kids to new things. Maybe they’ll say ‘Hey, I want to do that.’”