DePaul students and Emiliano Zapata Sur residents continue a 12-year partnership in Mexico

DePaul students and Emiliano Zapata Sur residents continue a 12-year partnership in Mexico

Three years ago, DePaul alum Daniel Alanis spent six months

in Mérida, Mexico studying

Spanish, taking courses, and engaging with families in the neighborhood of

Emiliano Zapata Sur (EZS). Mérida,

also known as the Maya town of T’ho, is the commercial and cultural capital of

the Yucatan Peninsula. Spanish conquistadores destroyed the city in 1542 and

built on top of the ruins, naming the new town Mérida after the one in Spain. While the first language of

most present-day residents is Spanish, the city still has the highest percentage of

indigenous Mayan speakers in Mexico. EZS is primarily

inhabited by Mayan-speaking migrants from Yucatan towns and villages. The

tightly knit nature of the community they form, especially among the women who

hosted Daniel’s community-based experience, had a life-changing impact

on him.

“It’s hard to imagine what kind of path I’d have if I hadn’t

gone there,” says Alanis. “It was like a fork in the road. I think of things ‘before

and after Mérida’.” Like many DePaul students who go on the program, the

experience taught him Spanish and about community engagement and social issues

in Mexico, but he also learned about the incredible assets created by residents

of EZS and especially about how they build community. For the past 12 years, the

Steans Center has partnered with Manos Unidas por el Sur de Mérida, a grassroots community organization

developed and run by women in EZS as a means to support their children and families.

Daniel represents a long line of students who have spent all or part of January

to June working on projects defined by Manos Unidas that are integrated with DePaul Community Service Studies courses. During the program, students engage in

numerous projects including garden work, tutoring, educational, technology and

social media workshops, research, and conversations with youth on Mayan

identity and language. In recent years, the work has centered around four community-based technology centers, Casas Digitales, developed by the women of Manos Unidas to provide computer access for youth. The computers are like magnets for young people who end up involving themselves in a variety of community programs supported by the organization. Because of such efforts, Manos Unidas was recently given official NGO status by the Mexican government.

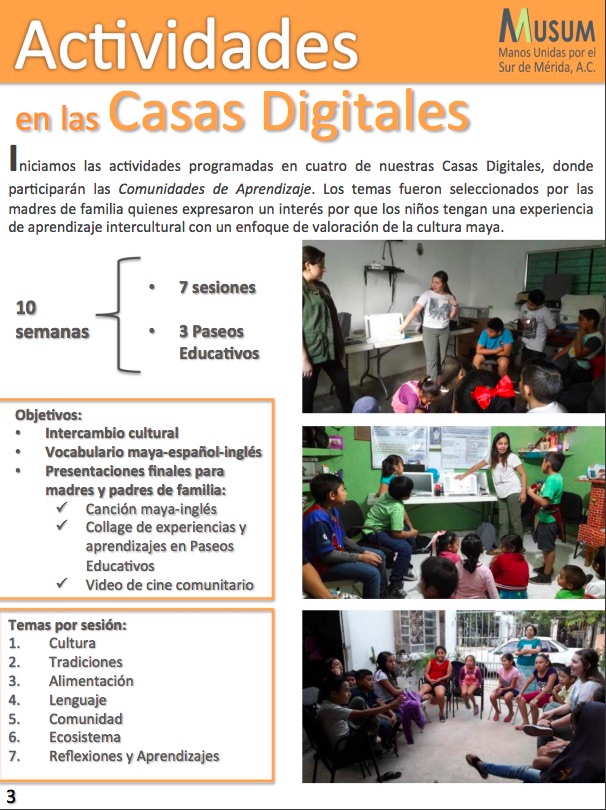

Manos Unidas Monthly Newsletter illustrating 2017 students leading workshops at the Cases Digitales of Manos Unidas. Boletín Musum Enero 2017 https://issuu.com/musum/docs/boleti__n_musum-enero_2017

Manos Unidas Monthly Newsletter illustrating 2017 students leading workshops at the Cases Digitales of Manos Unidas. Boletín Musum Enero 2017 https://issuu.com/musum/docs/boleti__n_musum-enero_2017

The Merida program is a collaboration between DePaul’s Study Abroad

office, the College of Liberal Arts and Social Science, the Department of Modern Languages, and the Steans Center. Each year

during Winter term (January to March), students are placed in homestays, study

Spanish at Universidad Autonoma de

Yucatán, take a relevant course from a DePaul faculty member in residence, and study Critical Community Engagement, the introductory course in the Community Service Studies minor, taught by faculty member

from Universidad Marista, a small Catholic university in suburban Merida. The

core assignment of that course is to spend at least one day per week working on projects

in EZS with Manos Unidas. During the Spring term (April to June) the program

offers students the option to stay in Mérida

to study Spanish and engage in a paid internship at a local NGO. The Spring course

and program focus a critical lens on the role of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and

allow students to explore the complexities of working at the community

level in the field of international development.

Arturo Caballero, the program’s service learning coordinator

for much of the past 12 years, says “service learning is an excellent

pedagogical approach. It’s experiential learning with interaction between

different cultures. It is reflection and action. And it is a learning community

of families, students and teachers.” Caballero capped off his tenure as service learning coordinator by co-authoring a book chapter with the former Associate Director of the Steans Center, Marisol Morales, about the theoretical underpinnings of the program in Asset-based Community Development and Integral Human Development. The concepts they outline are certainly reflected in the

experience of students like Alanis. “I came out of the experience virtually

fluent in Spanish, and had a very different experience working with mothers and

kids than I thought I would,” he notes. Alanis says that while the families he

encountered live simply, he learned about their considerable assets that go

beyond material wealth. “The people you are working with already have a lot of

what they need. Obviously, there are issues with people living in poverty, but

this is an extremely tight knit community. There was an element of community

I’ve never seen in America.”

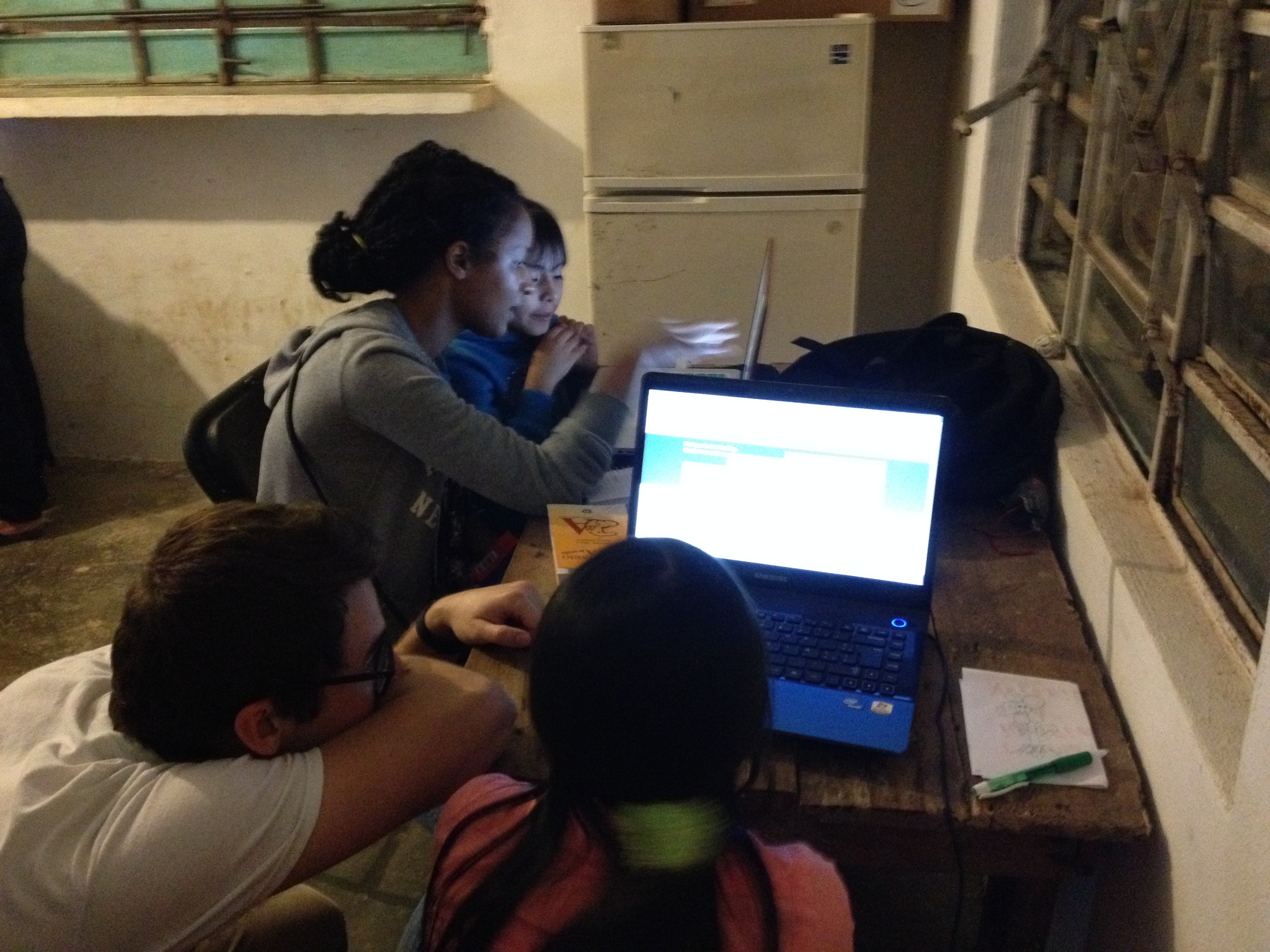

Daniel Alanis works with youth at Manos Unidas - Winter 2014

Daniel Alanis works with youth at Manos Unidas - Winter 2014

Howard Rosing, Executive Director of the Steans Center, notes

that the program “has developed along with the community in EZS. Students

can have a rich and meaningful learning experience – an experience that deeply connects

them with the community and especially the women and children. They see firsthand

the resiliency of communities that face challenging living conditions and how women

in the community have organized to resist such conditions. They see how people

organize to create assets – from a group of women informally organizing to

support families over a decade ago to today where Manos Unidas is a legally recognized NGO supporting sustained programming for youth and adults. And DePaul

students have contributed to and learned from that process the whole way.”

The long-term partnership between DePaul and residents of

EZS is meaningful for both students and residents. Erica Spilde, former program

manager for program, explains how the program fosters lasting memories and

connections for both the community members and for the students. During one of Spilde’s

visits to Mérida she recalls, “I

had a good opportunity to chat with a woman who is a leader in the community.

She got out a photo album and pointed out DePaul students she knew seven years

ago. There were pictures of students with community members. She remembered

names, and some of these students had come back to visit.”

The sentiment that DePaul students are positively

influencing the community in EZS is widespread among the women of Manos Unidas.

They repeatedly talk about the importance of their children being exposed to “cultural

differences” through the program and how it builds the confidence of youth when

they go to school. Elena Espinosa May, the Director of Manos Unidas, remembers how when the

students leave everyone says, “I’m not going to cry, I’m not going to cry.” And

then “the tears come streaming down, and they say, ‘I’m not going to cry!’ and

I say to myself, ‘I’m not going to cry, because you’ll come back.’ Yet the impact

of the students, according to Espinosa May, is more than emotional. She notes, "first I

said to the boy who came from DePaul, ‘they look up to you as role models.’ [They

say] ‘When I’m big, I’m going to be like this one, like that one,’” Most

importantly, she notes, because of the DePaul students “they [neighborhood youth]

all want to get in line to walk into class [school]. There’s a big difference.”

This is real-life engagement, it isn’t scripted. It allows students to engage authentically on an everyday level.

That the relationship between DePaul students and EZS residents

is mutually beneficial is not surprising to Jacqueline Lazú, Associate Dean in the College of Liberal Arts and Social

Sciences which oversees the Mérida

curriculum. Lazú, who is also an

Associate Professor in Modern Languages and used to direct the Community

Service Studies program, says “This is real-life engagement, it isn’t scripted.

It allows students to engage authentically on an everyday level.”

DePaul students study Critical Community Engagement at Universidad Marista

DePaul students study Critical Community Engagement at Universidad Marista

The importance of the cultural exchange in the Mérida program is apparent to Nila Ginger

Hofman, Professor of Anthropology and Faculty Director of Community Service

Studies. She participated in the Merida Program in 2011 as a faculty member in

residence. During her stay, she taught a course on the anthropology of gender

that guided students toward more deeply understanding the gendered nature of

community life in Mérida and

EZS. This meant guiding students to understand ethnographically how people place meaning

on the world around them, including the women in EZS. “International educational partnerships of this type offer the quintessential form experiential learning for both students and community members. They illuminate the connection between global issues and everyday lived experience," says Hofman.

As Rosing states, "The success of DePaul’s approach to international community engagement rests on the act of listening to community members and forgetting for a moment about our own interests.” From the beginning of the relationship with Manos Unidas, Steans Center staff have

visited EZS annually to work with local coordinators to engage in listening to

what the women in the community want students to work on. Rosing and others still

visit every year to meet with local coordinators such as Claudia Chapa Cortes,

who manages the logistics of the study abroad program for DePaul in Mérida. From

her vantage point, she notes, “DePaul has a very distinctive approach in terms

of service learning. Many universities are looking for a volunteer-type situation.

But with the Steans Center, it is based on the assets of the community. The

community learns from students and students learn from the community. It’s not

like giving aid to the community.”

Professor Jaqueline Tapia Chavez of Universidad Marista, who

currently teaches Critical Community Engagement for DePaul sees firsthand how the students learn from their engagement. “I teach them the theoretical framework of this subject, and then the next day

they are in the community. In the end, students are more open to their

experience and are more tolerant of other perspectives. They understand pretty

well that learning doesn’t just happen at the end [of the experience]. It

happens during the whole process.” That learning process continues after the program ends. DePaul

alum Adam Penney, who graduated with a B.S. in Environmental Studies and a

minor in Spanish, studied in Merida in 2015. During the Spring term, Penney

spent four days a week teaching computer literacy to community members. “It was

humbling,” he says. “I benefited from the chance to build relationships with

people from different backgrounds and being in a new space. Being out of my

comfort zone let me see things in a different way.” He adds that the experience

changed the way he saw service. “It can be frustrating and complicated, and it

requires a lot of patience.” Now, as an urban agriculture instructor at Gary

Comer Youth Center on Chicago’s south side, he says his approach to his job

reflects what he learned in Merida. “I make fewer assumptions than I would have

before going to Mérida,” he says.

“I’ve learned how to work with people in a group who have different levels of

literacy and skill.”

It helped me realize a lot of practical things about how grassroots groups are run, who makes the decisions and how they work to engage communities.

For Kayla Walker, who majored in Peace, Justice and Conflict

studies, studying in Mérida enhanced

her understanding of nonprofit organizations. “It helped me realize a lot of

practical things about how grassroots groups are run, who makes the decisions

and how they work to engage communities.” As an intern during the Spring 2016

program, she worked on a manual on how nonprofits can create a volunteer infrastructure

for an organization that helps smaller groups such as Manos Unidas gain

administrative skills. Through the experience, she gained a more nuanced

understanding of how NGOs operate in Latin America both in terms of their

strengths as well as the barriers they create to social change.

Kayla Walker, Morgan Krause and the 2016 Merida Program students

Kayla Walker, Morgan Krause and the 2016 Merida Program students

Morgan Krause, an anthropology and Spanish major was part of

the cohort with Walker. She remembers a service learning experience when she

and other students worked with kids in the community. “We had a reflection with

kids in a forest on the coast, but we did it in a kid-friendly way – kids got

dirty, played, worked on a puzzle. We tried to do it in a way that allowed the

kids to share their own ideas and perspectives.” This experience prepared her

for the Spring internship where she worked on a virtual library for the youth

that provides resources for math, science and other skills. “In the end,” she

says “this experience has been a great opportunity to learn about a community,

its people, the issues they face – and about myself.”

For students and alum like Alanis, Penney, Walker and

Krause, fluency in Spanish is a skill they carried away with them from the

Merida program. But that fluency is built on a type of immersion in community

that helped them understand the cultural dynamics of life in urban Mexico and the importance of community building in such settings. The students felt

welcome into a unique cultural space—a space organized by Mayan-speaking women on the

periphery of a Mexican city—that they otherwise would have never experienced. The residence of EZS, in turn, benefit each year from engaging with a diverse group of college students, some whose families are from Mexico. They see increased confidence in their children that helps the youth in school and life. Consequently, the program has produced

powerful memories for community members and generations of students. As Mano Unidas Director Espinosa May notes, “they all say

they’re going to come back the next year. And they often do.”

Students interested in the program should visit the DePaul Study Abroad website.

Acknowledgement: Dan Baron, Steans Center Writer