This fall, student research, photos and reflections about the Black

Metropolis are brought to life in the new scholarly work, The Way They

Saw It: The Changing Face of Bronzeville (Dorrance Publishing Company).

The Way They Saw It builds on Horace Clayton and St. Clair Drake’s

landmark study of the neighborhood, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro

Life in a Northern City, published in 1945.

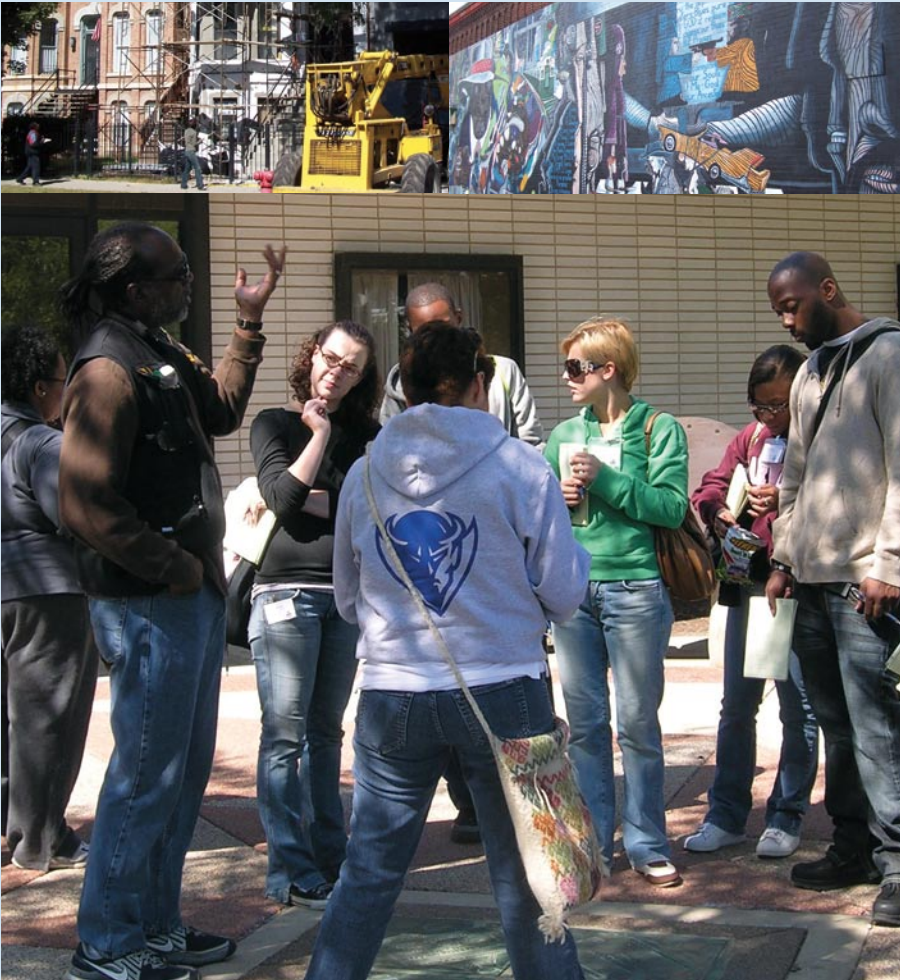

The Black Metropolis Project, a long-term collaboration between

Professor Ted Manley (Sociology) and the Steans Center, focuses on the

transformation of Bronzeville. The Project and They Way They Saw It are

prominently concerned with a different kind of transformation, the kind

that happens when students are engaged in a service learning project that

transforms their perceptions of a subject and a neighborhood. The Black

Metropolis Project embodies a service learning model focused on intensive

community-based research conducted by students—research that draws

from sociology, history, economics, the arts and many other disciplines.

Three DePaul students who contributed to the book shared thoughts about

this experience and what it meant to their academic life at the university.

Doreen Hopkins

Native to the South Side, Doreen Hopkins was no newcomer to Chicago

when she first took a class on the Black Metropolis. “The Project gave us a

different lens to look at the things we saw. DePaul is full of commuter

students and transfer students—many of whom have grown up in Chicago.

We take trains and buses—we see neighborhoods changing every day. What

this experience gave me was a different pair of glasses to look at the city.

Now, when I see a billboard, or a housing development, or a new Starbucks,

I ask different questions about that neighborhood. You can’t go out and

collect data and think ‘That was just for class,’ because we would see evidence of the same thing when we went home.”

Hopkins, who graduated from DePaul in 2001

and majored in Psychology, now works for the McNair

Scholars program at DePaul. She adds that learning

about Bronzeville through this project was significantly

different than being in a classroom. “When you are in

a classroom, you expect lectures, facts,” she says. “You

are supposed to learn material and take a test. This class

made everything current. I remember how we used to

go out on Saturday mornings to do field work—walk the

street and record what we saw on a pad of paper. If there

was an empty parking lot, we would estimate the address

for that. From week to week, we might even see the

neighborhood changing. It was happening right in front

of us. At the same time, we talked with residents who

wanted to share their story. They were excited to see us.”

Matthew Murphy

Matthew Murphy, who graduated from DePaul with

a marketing degree last spring, vividly recalls taking

digital pictures in Bronzeville of landmarks, changing

landscapes, housing and businesses.

Just as indelible as those photos, he says, is the

way his preconceived images of Bronzeville and the

South Side changed because of this project. “Outside

of going to Sox games, I had never crossed the Dan

Ryan,” says Murphy. “This was a whole different world

for me. On top of that, I never thought I’d go into public

housing units. The first time I went to

Bronzeville, I was kind of scared. It felt

strange walking around with a camera

in what was a new world for me.”

The process of observing and

learning that comes through in

The Way They Saw It was a key part

of the learning process for Murphy.

“I listened, and that really made a

difference in my academic career

at DePaul. It’s easy to treat people as subjects, especially

if you are looking to have them fit specific stereotypes.

But a lot of it was about listening.”

Murphy says The Way They Saw It, like the rest of

this project, provides a “necessary tool” for studying

Bronzeville. “In essence, if you only go by secondary

research, books or statistics from a census, you will

never know firsthand what happened in a community.

To actually be there and think about issues—that was a

great experience.”

Molly Szymanski

Some students who contributed to this book and are

already on a path to working with urban communities say

the project provided them with invaluable experiences.

“This Project solidified my passion for working with urban

populations and the economically disadvantaged. It gave

me knowledge and tools,” says Molly Szymanski, who is

pursuing a master’s in public service at Marquette

University in Milwaukee. Working on the book and

Project not only exposed her to the community—

it allowed her to learn a wide range of skills. “Through

the project, I learned so many skills,” she says, “including

geographic mapping, data entry, qualitative research,

how to conduct interviews, how to organize meetings

at the public library. And, because I was also a teaching

assistant, how to work with students.”

For Szymanski and many other students who

produced this book, the experience had an impact on

how she learns and how she views the city. “Going out

and getting that firsthand data—actually walking the

streets—you are gathering information, not just reading

about what happened. Because of this Project,

I definitely have become a more attuned observer of

my environment. Your city as you see it gets bigger,” she

adds. “It’s not just the four blocks near where you live or

go to school.”

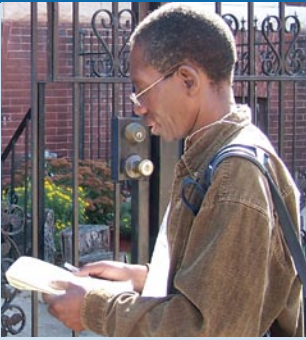

In her senior year at DePaul, Szymanski worked

with Manley and the late

Caleb Dube (right) to select

photos for the project and

collaborate on the development of its editorial content.

This fall, student research, photos and reflections about the Black

Metropolis are brought to life in the new scholarly work, The Way They

Saw It: The Changing Face of Bronzeville (Dorrance Publishing Company).

The Way They Saw It builds on Horace Clayton and St. Clair Drake’s

landmark study of the neighborhood, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro

Life in a Northern City, published in 1945.

The Black Metropolis Project, a long-term collaboration between

Professor Ted Manley (Sociology) and the Steans Center, focuses on the

transformation of Bronzeville. The Project and They Way They Saw It are

prominently concerned with a different kind of transformation, the kind

that happens when students are engaged in a service learning project that

transforms their perceptions of a subject and a neighborhood. The Black

Metropolis Project embodies a service learning model focused on intensive

community-based research conducted by students—research that draws

from sociology, history, economics, the arts and many other disciplines.

Three DePaul students who contributed to the book shared thoughts about

this experience and what it meant to their academic life at the university.

Doreen Hopkins

Native to the South Side, Doreen Hopkins was no newcomer to Chicago

when she first took a class on the Black Metropolis. “The Project gave us a

different lens to look at the things we saw. DePaul is full of commuter

students and transfer students—many of whom have grown up in Chicago.

We take trains and buses—we see neighborhoods changing every day. What

this experience gave me was a different pair of glasses to look at the city.

Now, when I see a billboard, or a housing development, or a new Starbucks,

I ask different questions about that neighborhood. You can’t go out and

collect data and think ‘That was just for class,’ because we would see evidence of the same thing when we went home.”

Hopkins, who graduated from DePaul in 2001

and majored in Psychology, now works for the McNair

Scholars program at DePaul. She adds that learning

about Bronzeville through this project was significantly

different than being in a classroom. “When you are in

a classroom, you expect lectures, facts,” she says. “You

are supposed to learn material and take a test. This class

made everything current. I remember how we used to

go out on Saturday mornings to do field work—walk the

street and record what we saw on a pad of paper. If there

was an empty parking lot, we would estimate the address

for that. From week to week, we might even see the

neighborhood changing. It was happening right in front

of us. At the same time, we talked with residents who

wanted to share their story. They were excited to see us.”

Matthew Murphy

Matthew Murphy, who graduated from DePaul with

a marketing degree last spring, vividly recalls taking

digital pictures in Bronzeville of landmarks, changing

landscapes, housing and businesses.

Just as indelible as those photos, he says, is the

way his preconceived images of Bronzeville and the

South Side changed because of this project. “Outside

of going to Sox games, I had never crossed the Dan

Ryan,” says Murphy. “This was a whole different world

for me. On top of that, I never thought I’d go into public

housing units. The first time I went to

Bronzeville, I was kind of scared. It felt

strange walking around with a camera

in what was a new world for me.”

The process of observing and

learning that comes through in

The Way They Saw It was a key part

of the learning process for Murphy.

“I listened, and that really made a

difference in my academic career

at DePaul. It’s easy to treat people as subjects, especially

if you are looking to have them fit specific stereotypes.

But a lot of it was about listening.”

Murphy says The Way They Saw It, like the rest of

this project, provides a “necessary tool” for studying

Bronzeville. “In essence, if you only go by secondary

research, books or statistics from a census, you will

never know firsthand what happened in a community.

To actually be there and think about issues—that was a

great experience.”

Molly Szymanski

Some students who contributed to this book and are

already on a path to working with urban communities say

the project provided them with invaluable experiences.

“This Project solidified my passion for working with urban

populations and the economically disadvantaged. It gave

me knowledge and tools,” says Molly Szymanski, who is

pursuing a master’s in public service at Marquette

University in Milwaukee. Working on the book and

Project not only exposed her to the community—

it allowed her to learn a wide range of skills. “Through

the project, I learned so many skills,” she says, “including

geographic mapping, data entry, qualitative research,

how to conduct interviews, how to organize meetings

at the public library. And, because I was also a teaching

assistant, how to work with students.”

For Szymanski and many other students who

produced this book, the experience had an impact on

how she learns and how she views the city. “Going out

and getting that firsthand data—actually walking the

streets—you are gathering information, not just reading

about what happened. Because of this Project,

I definitely have become a more attuned observer of

my environment. Your city as you see it gets bigger,” she

adds. “It’s not just the four blocks near where you live or

go to school.”

In her senior year at DePaul, Szymanski worked

with Manley and the late

Caleb Dube (right) to select

photos for the project and

collaborate on the development of its editorial content.

The book is dedicated to

Dube, a former visiting

professor in the Department

of Sociology and, later,

principal investigator for the

Black Metropolis Project. The book credits Dube for his

“unfailing commitment, devotion and passion for African

American culture.”

Community as Partner

Manley and students who participated in the Black

Metropolis Project worked closely with a range of

community partners, including several libraries on the

South Side where “town hall” meetings on the project

were held. According to Sherri Ervin, Head Librarian

at the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago

Public Library, “This Project encouraged people who were

interested in the changes occurring in Bronzeville to come

together. Anything that has a direct impact on community

residents as it relates to housing, education and other key

issues—that’s important for people to know about.”

Meanwhile, this new book not only depicts how

history transforms a community—and the students who

learn about it. Manley says that The Way They Saw It

could also serve as a learning tool for students, schools

and organizations that want to understand a neighborhood’s history and how it is changing. “This book, and the

Black Metropolis Project, demonstrate how students can

learn about a community by documenting the history of

that community. The Way They Saw It shows how service

learning plays a key role in the academic experience of

students—while contributing to what we know about the

Black Metropolis.”

The book is dedicated to

Dube, a former visiting

professor in the Department

of Sociology and, later,

principal investigator for the

Black Metropolis Project. The book credits Dube for his

“unfailing commitment, devotion and passion for African

American culture.”

Community as Partner

Manley and students who participated in the Black

Metropolis Project worked closely with a range of

community partners, including several libraries on the

South Side where “town hall” meetings on the project

were held. According to Sherri Ervin, Head Librarian

at the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago

Public Library, “This Project encouraged people who were

interested in the changes occurring in Bronzeville to come

together. Anything that has a direct impact on community

residents as it relates to housing, education and other key

issues—that’s important for people to know about.”

Meanwhile, this new book not only depicts how

history transforms a community—and the students who

learn about it. Manley says that The Way They Saw It

could also serve as a learning tool for students, schools

and organizations that want to understand a neighborhood’s history and how it is changing. “This book, and the

Black Metropolis Project, demonstrate how students can

learn about a community by documenting the history of

that community. The Way They Saw It shows how service

learning plays a key role in the academic experience of

students—while contributing to what we know about the

Black Metropolis.”