In the past few decades, higher education has seen a paradigm shift: the idea of college as a place for providing instruction has largely been reimagined as a place for producing learning (Barr and Tagg 1995). Research in the emergent and interdisciplinary field known as the learning sciences has been a key factor in this shift. Scholars in this field have been able to identify and advance a more scientific understanding of learning and cognition by drawing from disciplines as diverse as cognitive neuroscience, human-computer interaction, linguistics and sociology.

As a part of this changing landscape, experts in curriculum design and other fields have designed a number of teaching and learning frameworks or models. These frameworks are informed by research and can serve as guidelines or conceptual maps for instructors and departments engaging in designing or redesigning courses. Two teaching and learning frameworks that complement each other well are Backward Design and Universal Design for Learning.

Backward Design

Shortcomings of "Traditional Design" Approach

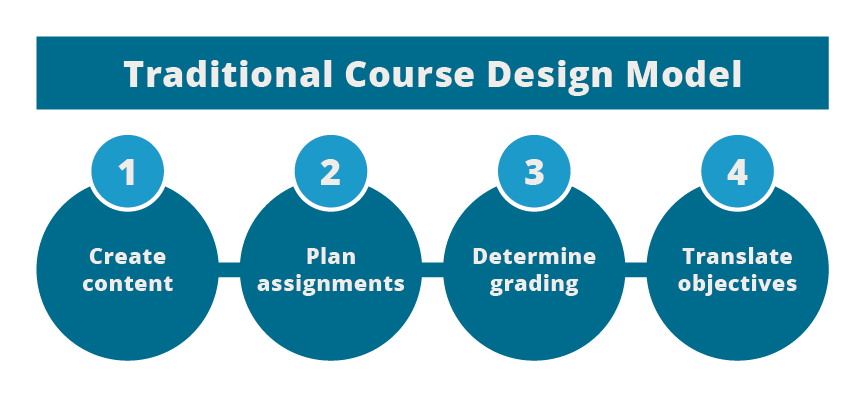

Many instructors begin designing their courses with a focus on content, such as the texts and readings you will ask your students to complete. This process typically looks something like the following:

- Create or adapt course content.

- Plan the assignments and tests.

- Determine the grading procedures.

- Translate course content into instructor-focused objectives for syllabus.

But as Wiggins and McTighe argue in their book Understanding by Design, this approach to course design has two limitations:

- It often leads to adopting learning activities that often do not have a valid educational purpose. That is to say, the activities are chosen not because they lead to specific, desired learning but because they are fun or interesting. This is not to say that fun and interesting activities are incompatible with having an articulated educational purpose as the two things are not mutually exclusive.

- It often leads to attempting to cover all factual material in a short timeframe (often 10 weeks at DePaul) without highlighting the big ideas or most important takeaways— the “why” of learning.

The "Backward Design" Approach

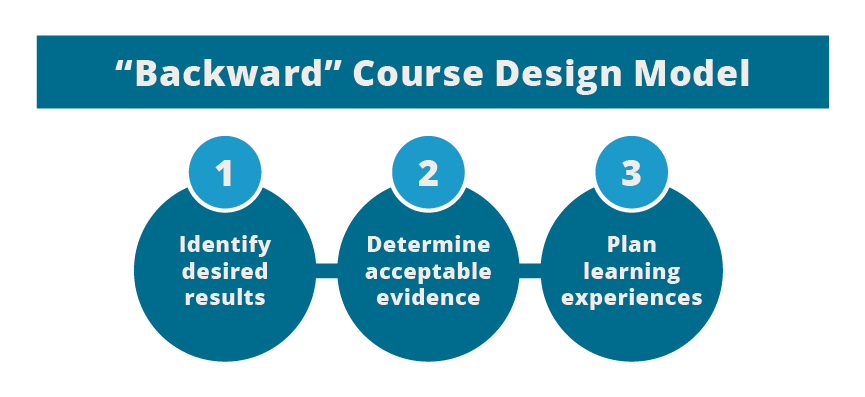

In order to overcome these shortcomings, Wiggins and McTighe argue for a curriculum planning process they call "backward design," which involves three steps:

- Identify desired results. By the end of your course, what knowledge/skills/abilities should your students possess?

- Determine acceptable evidence. What forms of evidence can you use to document and assess your students’ learning?

- Plan learning experiences and instruction. What activities and instruction will you provide in order to assist students in adequately demonstrating their learning?

If you'd like more information on Wiggins and McTighe's work, you might want to start by reading

an introduction to the Understanding by Design framework published by the ASCD.

Universal Design for Learning

The

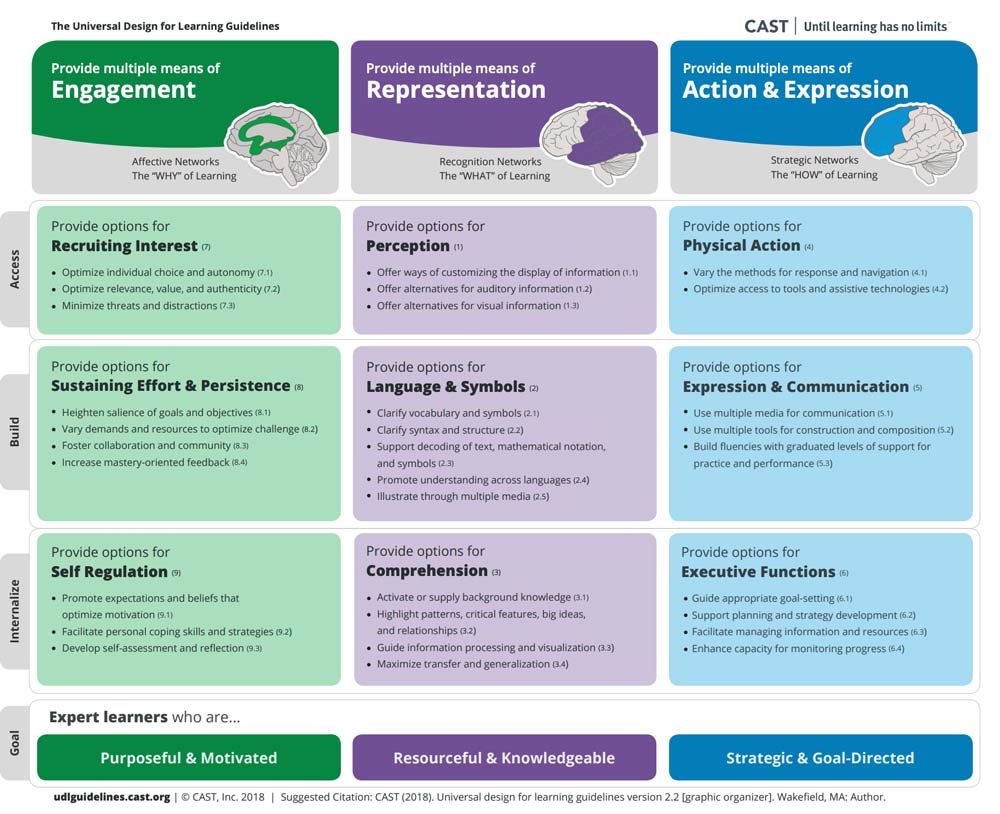

Universal Design for Learning framework, which grew out of the larger universal design movement, has been shown to be an effective approach to designing learning experiences that are accessible to all students, including English language learners, students with disabilities, and students with differing educational and cultural backgrounds. The framework involves three domains and a number of specific guidelines. Instead of listing each guideline below, some examples of how the guidelines might be followed are given.

The Universal Design for Learning graphic organizer is a helpful guide to putting its concepts in practice.

The Universal Design for Learning graphic organizer is a helpful guide to putting its concepts in practice.

Examples of Implementing UDL Guidelines in a Course

-

Engagement: Stimulate interest and motivation for learning. Some examples:

- Make your first day of class matter. Instead of simply introducing the syllabus, check students' knowledge of key course policies and deadlines with a quiz game. Use icebreakers to help you and your students begin creating an authentic learning community.

- Incorporate opportunities for students to engage with course concepts and one another. Intersperse learning activities such as "think-pair-share" and "discussion leaders" throughout lectures, or use software like PollEverywhere to add engagement to an otherwise passive activity.

- Encourage your students to adopt a growth mindset. Students with a growth mindset recognize that learning something new is difficult, but they also believe that their performance can improve with hard work, smart practice, and feedback.

-

Representation: Present information and content in different ways. Some examples:

- Supplement lectures and readings with multimedia, and make sure the multimedia is accessible to all learners by enabling closed captioning and providing transcripts.

- Be clear about the vocabulary and symbols that are important in your discipline and in the course you’re teaching. Paraphrase jargon in simpler terms. Provide metaphors to draw parallels between an everyday concept and the more complex one you're teaching. Give students access to both your lecture materials and an alternate explanation of the same concept by another expert in the field.

- Don’t rely on idioms or unnecessary cultural references that may confuse (rather than instruct) English language learners.

-

Action & Expression: Differentiate the ways that students can express what they know. Some examples:

- Provide low-stakes opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning and receive constructive feedback prior to completing high-stakes assignments.

- Set clear expectations and provide examples that meet or exceed those expectations.

- Offer a variety of ways in which your students can demonstrate their learning. For example, give students options to compose in multiple media, such as text, speech, drawing, design, audio, or video.

You can learn more about this framework by visiting the

UDL Guidelines website, the UDL On Campus website, or reading Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice, either

on the web for free (requires registration) or

through I-Share.

Other Frameworks

-

Integrated Course Design by L. Dee Fink (IDEA Paper No. 42) is a five-step system that provides a conceptual framework for determining course goals, activities, and student assessment when creating and evaluating an integrated course design.

- More common in corporate and vocational training contexts are models such as ADDIE,

SAM, and

Kirkpatrick.

Taxonomies of Learning

Taxonomies of learning are attempts by scholars to characterize different types of learning, much like how scientists use taxonomies to classify different species of organisms. Similar to how Carl Linnaeus established what came to be the modern system of classifying organisms, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom and a number of his colleagues proposed a system of classifying educational objectives1 that has become ubiquitous.

According to Bloom, there are three domains or basic types of educational objectives:

- Cognitive, involving mental processes such as memory recall and analysis;

- Affective, involving interest, attitudes, and values; and

- Psychomotor, involving motor skills.

Bloom and his colleagues focused first on the cognitive domain, outlining six levels of objectives that build upon one another:

- Knowledge, or the ability to remember and recall things;

- Comprehension, or the ability to understand and interpret things;

- Application, or the ability to use knowledge and comprehension to solve new problems;

- Analysis, or the ability to identify patterns, relationships and structures of things;

- Synthesis, or the ability to combine smaller elements of things to create larger thing; and

- Evaluation, or the ability to make judgments about a thing.

Revised Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom's taxonomy was revised in 2000 by Lorin Anderson, one of Bloom's former students, and one of Bloom's original collaborators, David Krathwohl. The revised taxonomy is, generally speaking, what most educators refer to when referencing Bloom's taxonomy. One of the more significant changes was their placement of "creating" at the top of the pyramid3. In Bloom's original taxonomy, "evaluation" was considered the highest level of cognition, with "synthesis" immediately below it. To reflect changes in teaching and learning scholarship and practice, Anderson and Krathwohl renamed synthesis to "creating" and moved it to the top of the cognitive hierarchy.

In adding the knowledge dimension, Anderson et al. establish four different kinds of knowledge:

- Factual knowledge, which are basic elements to a discipline students need to know or solve problems in;

- Conceptual knowledge, which refer to the connections between the basic elements within a larger whole that allow them to function together;

- Procedural knowledge, which relates to the steps in knowing how to perform a task or pursuing a method of inquiry; and

- Metacognitive knowledge, which consists of knowledge about cognition generally in addition to one's own cognitive processes.

By including the last type of knowledge—metacognition—the authors underscores the importance of students' awareness of their own thought processes, a point at which both cognitive and social constructivist models of learning converge.

Fink's Taxonomy of Significant Learning

One popular alternative to Bloom's taxonomy is L. Dee Fink's Taxonomy of Significant Learning. Unlike Bloom's original and revised taxonomies, Fink's is non-hierarchical, with each element interacting with one another to "stimulate other kinds of learning" (Fink 2005). Fink also includes elements that would be classified as "affective" under Bloom's taxonomy, such as "caring" and "the human dimension." Similar to the revised Bloom's taxonomy, Fink recognizes the importance of metacognition as a dimension of learning.

The Six Dimensions of Fink's Taxonomy

Understanding key ideas, information, and perspectives

Cultivating critical, creative, and practical thinking skills

Recognizing connections between information, ideas, perspectives, and lived experiences

Learning about oneself and others

Developing new feelings, interests, and values

Becoming self-directed, lifelong learners

For more on Fink's Taxonomy, you can

borrow his book

Creating significant learning experiences : an integrated approach to designing college courses from DePaul's library.

References

Barr, R., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning—a new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27(6), 12-25.

Englehart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. (B. S. Bloom, Ed.). New York: David McKay Company.

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (2012). Universal design for learning in the classroom : practical applications. Guilford Press.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.